The article discusses the causes and circumstances of the resettlement of Ossetians to the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, characterizes the socio-economic and political situation of the Ossetian diaspora in the Middle East in the Ottoman period and in modern times.

Reasons for the resettlement of Ossetians in the Middle East.

Single migrations of Ossetians to the countries of the Middle East took place as early as the Alanian era and were carried out mainly along the centuries-old established channels of the Black Sea slave trade. It is known, for example, that among the Circassian Mamluks in medieval Egypt there were several individuals of clearly Alanian origin. It can be assumed that in later eras, individual representatives of the Ossetian ethnic group ended up as slaves or hired soldiers in the Ottoman Empire, Iran and the Arab countries, without standing out, however, from the general mass of the North Caucasians, referred to by the collective term "Circassians".

The relatively massive resettlement of Ossetians to the Middle East, which marked the beginning of the formation of the Ossetian diaspora, occurred only at the final stage of the Caucasian War and was one of the links in a much larger phenomenon - the exodus (partly voluntary, but mostly forced and violent) of the highlanders of the North Caucasus to the Ottoman Empire , the so-called muhajirism (from the Arabic muhajir "migrant").

The reasons and specific circumstances of Ossetian migration are known in their main features. In contrast to the Northwestern Caucasus, Muhajirism in Ossetia was not the result of an official policy of squeezing out or expelling the indigenous population. The resettlement here was rather a form of reaction of a part of the traditional Ossetian society to the forced establishment of a military-colonial regime in the region, which took on especially pronounced features after the final conquest of the Eastern Caucasus and the capture of Imam Shamil in 1859. Undoubtedly, to some extent, leaving for Ottoman Turkey can be considered as a deviation by certain groups of Ossetian society of the imperial variant of social modernization imposed on them.

Among the specific motives that prompted part of the Muslim Ossetians to leave their homeland, one can name fears regarding the possible confiscation of land in favor of the Cossacks, forced Christianization, forced recruitment, increased tax oppression, etc. These fears were largely exaggerated and often deliberately fanned by circles that had narrower, group reasons for striving to resettle in Turkey: partly by the mullahs, who feared a weakening of their influence on the flock against the background of the strengthening of the position of Christianity in Ossetia, partly by some representatives of the nobility, interested in protecting their traditional class privileges from the destructive impact of Russian agrarian reforms. At the same time, fears of this kind were not completely groundless, which is confirmed by the practice of the Russian authorities, including in Ossetia itself, for example, the liquidation shortly before the start of resettlement to Turkey of several lowland Ossetian villages, whose lands were allotted for Cossack villages. In addition, despite the fact that in Ossetia there was no direct expulsion of a potentially restless or unreliable “native element” from the empire, similar measures of the authorities taken in other areas of the region could not but be perceived by some Ossetians as Russia’s policy towards the mountainous Muslim the population as a whole, especially since there were circles in Ossetian society, albeit not numerous, who sympathized with Shamil's movement, and a certain number of Ossetians personally participated in it. In the last stages of the Caucasian War and after its end, it was precisely the representatives of these strata opposed to the Russian authorities that made up the most active and rather significant proportion of the Muhajirs. Summarizing what has been said, we can state that, regardless of the real intentions and policy of the government regarding the population of Ossetia (Ossetian District), among a certain part of it in the late 50s - early 60s. extremely negative expectations for the near future became widespread, prompting many Ossetians to make a decision to resettle in the Ottoman Empire. It should be noted that the latter, as a rule, was presented to them in an extremely idealized light as a powerful and prosperous state, ruled by a just and merciful sultan - the caliph of all Muslims. This circumstance, of course, also served as an additional incentive for resettlement for persons prone to a somewhat adventurous search for a "better life" in a foreign land.

composition of the migrants.

The above reasons largely predetermined the social composition of the settlers. A very noticeable group of them and, in a sense, an initiative core was formed by representatives of the traditional landowning aristocratic elite - the Aldars, Badeliats and others (it was the number of these classes in their homeland that suffered the greatest relative losses as a result of resettlement). At the same time, the nobility managed to captivate a considerable number of representatives of dependent estates - Kavdasards, Kusags, etc. The most numerous group of Muhajirs, however, were, as in their homeland, free Farsaglaq peasants.

It is obvious that the vast majority of immigrants were associated with agricultural production. At the same time, the available data make it possible to single out a few non-agrarian strata from their total mass - professional military (former officers of the Russian army), Muslim clergy.

During 1860–1861 17 Ossetian officers in the rank from cornet to captain moved to Turkey.

Among the migrants were representatives of both ethno-dialect groups of the Ossetian people - Iron and Digor. The Irons were represented mainly by people from the Tagauri society, and to a lesser extent from the Kurtatin, Alagir and Trutovsky societies, and residents of the lowland Muslim villages created in the previous decades - Zilgi, Shanaevo (now Brut), Zamankul, Tulatovo (now Beslan), Khumalag and others - in comparison with the inhabitants of the villages located in the areas of traditional localization of these communities in the mountains (from the mountain villages, the most noticeable number of Muhajirs was given by Dargavs, Saniba, Koban). The Digorian part of the Ossetian settlers were mainly residents of the village of Magometanovsky (now Chikola), as well as Tuganovsky (now Dur-Dur), Karadzhaevsky (now Khaznidon), Karagach and others.

In confessional terms, almost all migrants were undoubtedly Sunni Muslims, although the possibility of leaving for Turkey an insignificant number of nominal followers of Christianity or the traditional religion of the Ossetians is not ruled out.

Stages of resettlement and the number of Ossetian Muhajirs.

The main waves of migration of Ossetians to the Ottoman Empire - often simultaneously and together with representatives of other peoples of the Central and Eastern Caucasus - took place in the period from 1859 to 1862, and the peak of this movement occurred in the spring-summer of 1860, when up to 3 thousand Ossetians The next, much less significant stage of Ossetian muhajirism dates back to 1865, when, on the initiative and under the leadership of General Mussa Kundukhov, an Ossetian by nationality, more than 23 thousand highlanders, mostly Chechens, moved to Turkey, according to Russian official data, with whom migrated and about 350 souls of Ossetians (45 households). Subsequently, only individual migrations occurred sporadically.

In our opinion, in the period from the late 50's to the mid-60's. 19th century in total, hardly more than 5 thousand people left Ossetia for the Ottoman borders, some of whom returned back in the very first months and years after the resettlement. Informative for estimating the approximate number of Ossetian Muhajirs may be the information at our disposal on the number of Turkish Ossetians at a later time. So, the son of General M. Kundukhov, Bekir Sami Kundukh (Bekir Sami-bey), who was the Minister of Foreign Affairs in the first government of Kemalist Turkey, who visited Ossetia in 1920, noted that there were no more than 600-700 families or 6 thousand people in the country. Ossetian shower. By the beginning of the 70s. In the 20th century, according to experts from the North Caucasian Cultural Society in Ankara, 9,000 ethnic Ossetians lived in rural areas of Turkey, and approximately the same number was supposed to live in cities.

Migration routes.

The migration of Ossetians, as well as representatives of other Central and East Caucasian peoples, was carried out, as a rule, by land through the Darial or Mamison passes of the Main Caucasian Range, Georgian and Armenian lands directly to the border Kars sanjak of the Ottoman Empire. However, individual small shipments of immigrants were transported by sea from Batum to Trabzon and other Black Sea ports of Anatolia, or - more rarely - to Istanbul. The latter was usually practiced in respect of settlers who were wealthy or had a certain status prestige in the eyes of the Ottoman authorities, for example, clergymen, career officers, etc.

sanjak(district) - an administrative-territorial unit in the Ottoman Empire, which was part of vilayet(province). The borders of the former Ottoman sanjaks roughly correspond to the silts in modern Turkey.

Settlement of Ossetian settlers in the Middle East.

Muhajirism was not a one-time act for the majority of Ossetians. Due to various factors, primarily subsequent events of a military and international political nature, their search for places of final settlement on the territory of the Ottoman Empire turned out to be stretched out for years and decades. We can only trace these movements of Ossetian groups within the empire in general terms, since the separation of individual ethnic groups from the total mass of North Caucasian settlers is difficult due to the inaccuracy of the use of the Caucasian ethnic nomenclature in Turkish sources, in which all mountaineers were usually called Circassians or simply Muhajirs and were not always given - according to the reason for their practical irrelevance is their narrower, “tribal” characteristic. Reliable identification of Ossetians is possible only in a very limited number of Ottoman archival documents, which mention the Caucasian Muhajirs of the Digor tribe, or the Tegi tribe (i.e. Tagaurians). The fact that during this period there were no signs of a broader ethno-national self-identification of the Ossetians is noteworthy in itself, since to some extent it is a reflection of the nature of ethnic self-consciousness and the way of thinking of the settlers, primarily their leaders.

Judging by the available data, during the years 1859-1862. practically all Ossetian settlers were quite compactly settled in North-Eastern Anatolia, in the Kars sanjak, mainly in the mountainous and wooded area of Sarykamysh on the eastern slopes of the Soganly ridge, where there were significant areas of free land due to the migration of local Armenians and Greeks to Russia in previous decades. Ossetian immigrants created at least a dozen independent villages here (often on the site of the ruins of settlements abandoned by the former inhabitants), and in isolated cases - separate quarters in existing Turkish villages. In one of the Ottoman documents it is reported that by September 1861 in this area, on the plane of Hamamli-Duzyu, "Circassians of the Digor tribe" were settled in the amount of 400 families, i.e. at least 2 thousand people . The number of natives of other Ossetian societies stationed here should have been no less. The names of some of the Ossetian villages founded here during this period are known: Yukary-Sarykamysh (Upper Sarykamysh), Hamamly, Bozat, Oluklu, Selim, Alisofu, Khancherli, Karakurt, Agdzhalar and others.

Apparently, already in the early 60s. the Sarykamysh region acquired a special attraction for small groups of Ossetians originally settled by the Port in other parts of Anatolia, primarily due to the presence of relatively numerous colonies of their compatriots here and the attractiveness of natural and climatic conditions (including due to the well-known similarity of the local landscape with the Caucasian). Undoubtedly, the preference of the Kars-Sarykamysh region for Ossetians also stemmed from its proximity to the Russian border, since, probably, a fairly significant part of the immigrants admitted the hypothetical possibility of their return to their homeland, or at least maintaining certain contacts with relatives who remained there, and some even made corresponding more or less successful attempts. In addition, a significant factor in choosing this area was its relative geographical isolation and sparse population, which was very important in view of the initial orientation of the Mukhajir Ossetians to preserve their traditional socio-cultural image intact. It is these circumstances that explain the facts of repeated migrations here with the sanction of the authorities of individual small parties of Ossetians from the inner regions of Anatolia and even, according to oral tradition, from Istanbul. So, in 1862, a group of Ossetian-Digorians sent to the Sivas vilayet, mainly representatives of the nobility, turned to the Ottoman administration with a request to resettle in Sarykamysh, motivating their request by the favorable climate of this region for them and the fact that 160 families had already been settled there. their "subjects". At the same time, the authors of the appeal assured the authorities that they would not allow any of the mentioned families to express their intention to return to Russia, and if there were any, they would ensure the recovery from them of all the funds spent on their arrangement by the state and the population. Other groups of Ossetians also made repeated movements around Anatolia in search of the most suitable places for permanent settlement, ultimately also finding shelter in Sarykamysh.

It should be noted that the Ossetians were not the only North Caucasians in the area. In the same years, several thousand Avars, Laks, Kabardians and Chechens migrated to the Sarykamysh region and settled in the immediate vicinity of the Ossetians. It is curious that this colonization was carried out by the Turkish authorities in fact in violation of the agreement with Russia on the non-settlement of Caucasian highlanders in the provinces bordering on it. Moreover, despite the fact that during the immigration of 1865, the Russian authorities demanded that the Porte comply with this condition much more strictly, some of the Ossetians who migrated during this period also settled in the villages previously created here by their tribesmen. Thanks to such an intensive influx of population from the North Caucasus, Sarykamysh already in the early 60s. was separated into an independent administrative unit - kaza (county) - as part of the Kars sanjak. According to a British military intelligence officer who visited Sarykamysh a few years later, more than 1,000 families of North Caucasians lived there, capable of fielding 2,000 mounted volunteers for the Ottoman army in case of war.

Outside of North-Eastern Anatolia, it is reliably known about the creation in the 60s. 19th century only one Ossetian settlement - the mixed Ossetian-Kabardian village of Batmantash in the sanjak of Tokat in Central Anatolia, where Mussa Kundukhov settled in 1866 or 1867 along with his closest associates, relatives and dependent people.

This picture of the settlement of Ossetian migrants on Ottoman territory remained unchanged for a little more than a decade and a half and was violated only as a result of the Russian-Turkish war of 1877–1878, when the Kars region was occupied by Russian troops and then included in the Russian Empire. under the name of the Kars region.

Following this, the vast majority of Ossetian colonists chose to leave the Russian Kars region and in the late 70s - early 80s. gradually migrated deep into Ottoman territory. The adoption of such a decision by the bulk of the Sarykamysh Ossetians and other North Caucasians, apparently, was influenced by the anti-Russian attitudes formed during the Caucasian war and the conviction based on them that it was impossible to preserve the traditional way of life and their ethnic and religious identity under the rule of the tsarist administration.

During these years, from a third to a half of the entire local Muslim population - Turks, Kurds, Turkmen-Karapapakhs, etc. - moved from the Kars region to the provinces remaining under the sovereignty of Istanbul. However, only among the North Caucasians this migration had the character of an almost universal outcome, which until recently the settlers were remembered as the "second Muhajirism".

According to the data of the statistical and geographical description of the Kars region undertaken by the Russian authorities, by the beginning of the 90s. 19th century in the Sarykamysh region, which was transformed into the Soganlug section, only three Ossetian villages remained: Upper Sarykamysh (23 households or 163 souls), Bozat (23 courtyards or 153 souls) and Khamamly (15 courtyards or 83 souls). The total number of Ossetians in rural areas of the region was 424 people. . And in 1897 the first general census of the population of the Russian Empire recorded 520 Ossetians in the entire Kars region. It should also be noted that during this period, a certain number of residents of these villages returned to Ossetia, and during the First World War, most of the Ossetians who remained in Sarykamysh fled to their historical homeland, fleeing fierce battles. However, in 1922, after the final transfer of the Kars region to Turkey, almost all of them (or their descendants) voluntarily resettled again, in accordance with the Soviet-Turkish agreement, to the places of their former residence in Sarykamysh. Finally, in the 20-30s. 20th century here, at the suggestion of the Turkish government, a part of the Ossetian families who migrated after the war of 1877–1878 also returned. to other Anatolian provinces, in particular, to Mush and Bitlis. All returned Ossetians were settled in three remaining villages (moreover, in Khamamly together with the Laks), as well as in the ss. Selim and Alisofu (in the latter, together with the Turkmen-Karapapakhs). These processes of return migration to the region to a certain extent restored (and for some time extended) the life potential of the Sarykamysh Ossetian community as one of the main local groups of the foreign Ossetian diaspora.

In the early 70s. 20th century at least 4,330 ethnic Ossetians lived in the villages of Kars province, mainly in the Sarykamysh region.

The second most important local Ossetian community in the Ottoman Empire was formed in the central part of the East Anatolian Highlands (or, according to the old terminology, in Turkish Armenia and Kurdistan) as a result of the migration of part of the Kars Ossetians there in the late 70s - early 80s. 19th century They founded a number of villages on a rather vast area north and west of Lake Van, of which, according to oral and documentary sources, the following are known to us: Simo, Khamzasheikh, Karaali, Govendik, Yaramysh, Mesdzhitli, Sarydavut in the sanjak of Mush; Hulyk, Aghjaviran (jointly with the Adygs) in the sanjak of Bitlis; Õrun in the sanjak of Siirt. As before in Sarykamysh, representatives of other North Caucasian peoples - Dagestanis, Vainakhs and Adygs often coexisted with Ossetians in this territory. However, in contrast to the former, rather compact settlement in Sarykamysh, here the colonies of the North Caucasians, including Ossetians, were dispersed in the form of small groups of villages or single settlements, usually located at a much greater distance (sometimes at a distance of many tens of kilometers) from each other. friend.

In the 20-30s. 20th century as part of the official campaign for the correction/Turkishization of the toponymy of Anatolia, some of these villages were renamed. So, Simo was named Kurganly, Khamzasheikh - Sarypynar, Karaali - Karaagyl, Mesjitli - Kyzylmesdzhit, Hulyk - Otluyazy, Agjaviran - Akchaoren, Yrun - Kayakhisar.

A significant part of the Ossetians after the war of 1877–1878. migrated from the Kars region in a western direction - to Central Anatolia, settling in this region even more dispersed, although against the "background" of a very numerous array of earlier North Caucasian (mainly Adyghe and Abkhaz-Abaza) colonies. Ossetian villages arose here during these years: Konakozyu, Yenikoy, Kapaklykaya, Kahvepynar (together with the Chechens), Dikilitash, Yenichubuk in the sanjak of Sivas; Chengibagy, Tashlyk (together with the Circassians), Kushoturagy (together with the Kumyks, Nogais and Circassians) in the Tokat sanjak; Boyalyk, Poyrazly, Karabadzhak, Kayapinar in Yozgat sanjak; Orkhaniye in the sanjak of Nigde; Fyndyk (together with the Kabardians, whose language the Ossetians switched to in the initial period of the settlement) in the Marash sanjak.

Renamed Gurpinar.

In addition to the above three main areas of relatively compact settlement of ethnic Ossetians in Anatolia, it is also known that one or two villages existed in the past in the Erzurum region.

In addition, a small group of Ossetians, after repeated movements across Anatolia, reached in the 80s. 19th century to Ottoman Syria, having founded there in the Kuneitra district, on the so-called Golan Heights, two settlements - Faraj and Fazara - in the immediate vicinity of the colonies of Adyghe, Abkhazian and Chechen immigrants.

Socio-economic and political situation of Ossetian immigrants in the Ottoman period.

In accordance with the legislation in force, the Ossetians and other North Caucasians who immigrated to the territory of the empire were provided with certain material assistance in order to turn them into a productive element of the population as soon as possible. As a rule, at the expense of the provincial budget and donations from local residents, a house was built for each resettled family, agricultural implements and draft animals were issued (usually a pair of oxen for two families), and daily food allowances were assigned for the period until the final settlement and harvest of the first harvest. The colonists were also exempted for several years from paying taxes and performing military service. At the same time, the Muhajirs who settled in Kars and then were forced to migrate from there to other provinces (to which the vast majority of Ossetians belonged) were granted these benefits twice, although the second time their volume and duration were noticeably shorter. It should also be borne in mind that when resettling both from the Caucasus and from the Kars region, Ossetians had the opportunity to take with them a significant part of their movable and immovable property, which minimized the likelihood of extreme poverty among them, comparable to the situation of migrants from the North-West Caucasus.

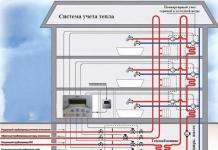

Nevertheless, the painless socio-economic adaptation of the Muhajirs in their new homeland was often hindered by rather significant unfavorable circumstances. Thus, the extremely harsh natural conditions of Sarykamysh (cold climate of the highlands and low level of soil fertility) limited the possibilities for effective agricultural production in this area, which immediately after the settlement prompted the Ossetians to look for alternative forms of economic activity. In particular, from the very first weeks of their stay here, the harvesting and sale of timber in Kars and Erzurum became the most important source of income for them, and this trade retained its importance over the next few decades and ceased to exist only due to the almost complete deforestation of local forests. Of the agricultural crops in Sarykamysh, only cereals (wheat and barley), potatoes, onions and some other vegetables grew, the harvest of which was only enough for the settlers' own consumption. The fields were fallow for two years. Fruit trees did not grow. The situation was better with the breeding of cattle and small cattle and horses, which was facilitated by the presence of a sufficient number of meadows and summer pastures. For wintering, however, all cattle were driven to the more southern lowland areas. Part of the animals, especially horses, was raised for sale, which was the most profitable item in the economy of the Ossetian population of Sarykamysh both before and during the Russian occupation of the region. Of the other products, only straw, hay and oil were exported and sold outside the villages. Separate facts of the occupation of the settlers by primitive individual entrepreneurship have been recorded. For example, it is known about the construction and commercial operation of a road crossing across the Araks River in difficult terrain near the village of Karakurt in the mid-70s. 19th century .

Judging by the Ottoman documents, from the very first years of settlement in the Kars-Sarykamysh region, some Ossetians and other people from the Caucasus, despite the exemption from military duty, were involved in voluntary paid service in the army and border units. So, already in 1860, the authorities announced the recruitment of 500 people "from among the population who arrived from Russia in the surrounding kaz" for security service in fortified posts being built along the border. During the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878, when the local Ossetian villages were at the epicenter of hostilities, a considerable part of their inhabitants joined the irregular "Circassian" cavalry formations and fought in their composition under the command of Musa Pasha (Mussa Kundukhov) and Gazi Muhammad Pasha (son of Imam Shamil). However, due to the poor provision of these detachments with ammunition and fodder and non-payment of salaries, many volunteers left them rather soon and returned to their villages.

At the initial stage of the Ossetians' residence in the region, there were cases of robberies by them of the local population, trade caravans, etc. However, as the colonists established economic life, this criminal activity lost its economic significance and began to decline. Its new surge took place after the occupation of the region by Russian troops. Finding themselves in uncertainty about their future and waiting for several years to resolve the issue of resettlement to Ottoman territory, the Ossetians “for a long time were not engaged in either arable farming or cattle breeding ...”, hunting “... by robbing livestock, mainly horses, which were driven abroad.” Only after the emigration of all who wished to the Turkish borders, the Ossetians who remained in Sarykamysh began to restore their economy and began to cultivate the land again.

The relationship between the Sarykamysh Ossetians and the surrounding Muslim population, despite certain frictions that took place in the initial period, were generally quite complementary. Most of the ethnic groups, next to which the Ossetians were located here, were themselves relatively recent migrants from the Russian Transcaucasia (karapapakhs) or neighboring regions of Anatolia (Kurds, part of the Turks), settled by the Porte in place of the emigrated Armenian and Greek population, and as a result did not have any rights and claims supported by historical tradition to the lands and economic lands allocated to the Ossetians. The political integration of the Ossetians and other North Caucasians into the local Muslim society was also facilitated by the significant predominance of the last settled agricultural element over the nomadic tribes in the structure. Relations between the colonists and local Christians, however, were initially more strained. After 1878, the conflicts between Ossetians and Armenians and Greeks settled by the Russian administration in villages abandoned by Muslims, including Ossetians, were especially acute.

The position of the Ossetians in the East Anatolian Highlands was somewhat different. The natural and climatic conditions of the Mush valley, where most of the Ossetian villages were located, were more favorable for agricultural activities, and the lands provided to them were more extensive than in the Sarykamysh region. However, here, too, mainly cereals were grown; in the production of other crops, the settlers were far inferior to the neighboring settled farmers - Armenians and Turks. Cattle and sheep in immigrant villages, as noted by modern observers, were quite numerous, but in this respect they lagged far behind the nomadic Kurds. At the same time, the Ossetians and other North Caucasians significantly outnumbered all local groups in terms of the quantity and quality of their horses, the breeding of which had a certain commercial value here as well. A significant number of Ossetians from the very first years of settlement in the region were involved in more profitable and prestigious non-agricultural activities. In particular, the settlers willingly joined the gendarmerie, the police, the Régi Tobacco Patrol and, to a lesser extent, the civil government. A considerable part was engaged in petty trade, as well as very profitable smuggling of tobacco. In general, the level of well-being of the local Ossetian community was undoubtedly higher than that of the surrounding population.

The relations of the Ossetians settled in Mush, Bitlis and Siirt with the main categories of the indigenous population were extremely complex, which stemmed from the weakness of the positions of official power here and the existence in the region of a system of exploitation (in the form of feudal-patriarchal “patronage”) of some ethno-social groups by others, consecrated by centuries of tradition. . At the head of this hierarchy were nomadic Kurdish tribes, then settled and non-tribal Kurds and other Muslim communities followed, while Armenians and other Christians occupied the lowest position. The Ossetians were initially considered by the leaders of the Kurdish tribes as an alien element, subject to either inclusion in the local hierarchy as a subordinate group, or displacement from the lands provided to them by the government. The “basis” for such claims was also the fact that almost all the colonies of the North Caucasians were created on the site of villages relatively recently abandoned by the Armenians, who were semi-serf dependent on the Kurds before emigration, which gave rise to the temptation of the latter to transfer their “ownership rights” to the new settlers. However, thanks to the rather rapid development by the settlers of effective mechanisms of mutual assistance, their better military-technical equipment and support from the provincial administrations, despite their small numbers, they managed to gain a foothold in the local ethno-social structure at a relatively high level, which assumed full autonomy in internal affairs and respect for personal freedom and dignity, albeit with certain forms of nominal "vassal" dependence on the most powerful tribes. However, the immigrants themselves often made predatory raids not only on Armenian villages, but also on the possessions of nomads, and at times participated as volunteers in the military-police actions of the authorities against the rebellious elements. On occasion, they pursued a completely independent local policy, even if it ran counter to the interests of their formal "suzerains".

An indicative illustration of the nature of the relationship between the Ossetians both with the Kurds and with the Armenians can be the conflict between the inhabitants of the village of Simo and the Sipkanly tribe, reflected in the report of the English consul, which occurred at the end of 1893 due to the fact that the Ossetians, against the will of the Kurds, agreed to conduct for a fee to the Russian border the Armenian families who emigrated from the nearby village of Lapbudag of the Hynys sanjak. On the way, a detachment of Kurds attacked the convoy with the aim of robbing the Armenians, but their escorts repulsed the attack, killing several attackers, and safely delivered their wards to the border. In response, the Kurds attacked Simo with large forces, and during the fighting that lasted several days, more than 20 people died there, mainly from the Kurds. However, since the position of the defenders was critical, they sent a messenger to the commander of the 4th Anatolian army, the Circassian Zeki Pasha, with a request to send troops to protect the besieged, which predetermined the outcome of the confrontation, favorable for the colonists. It can be assumed that the actions of the Ossetians in this episode were largely dictated by their desire to expand their own "living space" by developing the lands of the Armenians who left the region, which is confirmed by the fact of the subsequent Ossetianization of the village of Lapbudag.

In general, however, the fate of the Ossetian community located in Eastern Anatolia was in the Ottoman period an example of a predominantly independent struggle for survival in an extremely unfavorable ethno-political, socio-economic, and sometimes even natural environment. This situation changed only after the Kemalist revolution, when the central government strengthened its power over the eastern regions of the country, putting an end to the autocracy of the Kurdish feudal lords.

As for the Ossetian groups of Central Anatolia, their adaptation to local realities undoubtedly took place with much less complications due to fairly favorable natural conditions, a relatively high level of socio-economic development, and a more homogeneous and complementary composition of the population in relation to Caucasians (ethnically mainly Turkish). region. After endowing the material resources provided for immigrants and settling individual land disputes with the natives, the Ossetians pretty soon turned into a community mainly engaged in agricultural labor, although, as elsewhere in the country, a relatively high proportion of them entered the service of military, law enforcement and administrative institutions. . Neither Ottoman nor foreign documentary sources distinguish the Ossetians settled in the region from the total mass of the rather numerous North Caucasian (“Circassian”) element here.

Our information about the situation of the Syrian Ossetians is rather scarce. Undoubtedly, in the first period after the settlement, they, together with the inhabitants of the nearby Caucasian villages of the Golan Heights, were forced to defend their rights to the lands granted to them from the encroachments of the Bedouin and Druze tribes that were not controlled by the authorities. By the beginning of the 20th century, however, thanks to the stabilization of the socio-political situation in the Kuneitra region and special care from the administration, the local Circassian community turned into one of the most prosperous groups of the diaspora in the empire in socio-economic terms.

Most of the developed in the second half of the XIX century. On the Ottoman territory, local communities of Ossetians were ethno-socially quite isolated and closed, which was explained not only by the difficult nature of their “political” relations with a number of local peoples and the geographical isolation of many colonies, but also by significant differences in the socio-economic and cultural appearance of the settlers and the surrounding population, especially noticeable in the regions of Eastern Anatolia and Syria. In view of this, the inhabitants of the Ossetian settlements, as a rule, maintained a relatively limited level of sociocultural interaction with neighboring groups, with the exception of other North Caucasian communities. This situation undoubtedly contributed to the conservation of the forms of economic structure, social relations, culture and language brought from the Caucasus. A number of authors who visited the Muhajir colonies at the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. and later, a high degree of their adherence to the traditions and customs of their historical homeland is stated, in particular, their performance of ceremonial and labor rituals, observance of etiquette, the existence of remnants of the former class division, etc. At the same time, such a visible sign of the preservation of their ethnic identity by the settlers as the mass wearing of the Caucasian costume in everyday life, including the dagger and other elements of weapons, stands out in particular. It should also be borne in mind that, in general, during the Ottoman period, the authorities did not pursue pronounced assimilation goals in relation to ethnic minorities.

The position of the Middle Eastern Ossetians in modern times.

Starting from the 20s. In the 20th century, after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the emergence of a national state - the Republic of Turkey, the authorities of the latter began to carry out a very rigid policy of forced "melting" of all the country's ethnic groups in a pan-Turkish "melting pot". True, the real impact of this policy on the inhabitants of the Ossetian rural micro-enclaves was somewhat mitigated by the relative weakness of their economic contacts with the outside world, and in the east of the country by the small number of the Turkish population proper there. Undoubtedly, until the second half of the twentieth century. the majority of Ossetian local communities in Turkey were able, despite the unfavorable political and ideological background, to ensure the reproduction of their ethnic identity.

Made in the early 40s. Turkish ethnographer Suleiman Kazmaz, on the basis of field research in four Ossetian villages of Sarykamysh, records allow us to get some idea of the socio-cultural image of the local Ossetians and the nature of their identity during this period.

From this source it follows that at the time of the study, a total of 78 households lived in these villages, in the vast majority of Ossetian households.

In the collective consciousness of the inhabitants, the memory of origin from the Caucasus was clearly preserved with a noticeable tendency to idealize the historical homeland. As reasons for the exodus of ancestors to the Ottoman possessions, their unwillingness to live under Russian rule and the desire to preserve the Muslim religion were called. Ossetian remained the main language of everyday communication within the villages.

The houses were one-story buildings made of hewn stone and lime and, due to the scarcity of wood, had earthen floors and flat earthen roofs that poorly protected from moisture and cold. The stables were located outside the living quarters. The layout of the rooms was correct, and the interior decoration of the houses was distinguished by accuracy, cleanliness and decoration with a well-known aesthetic taste, which distinguished them from the background of the dwellings of representatives of other ethnic groups.

Of the traditional foodstuffs, the preparation of Ossetian cheese, pies-walibakhs, as well as dark beer on special occasions was recorded. A significant place in the diet was occupied by dishes of local and international cuisine. As a strong liquor, Turkish aniseed raki was consumed, but only by middle-aged and older people in moderation.

By the time described, the traditional costume had fallen out of use under the influence of the ban on wearing it by the republican authorities, in connection with which the villagers expressed regret.

Of the folklore genres, there were mainly heroic and abrec songs and fairy tales. Lyrical works were practically absent, being considered shameful. The epic tales have not been attested. Some poems by Kosta Khetagurov were known, including in the form of songs (for example, "Dodoi"), which, undoubtedly, was a consequence of close contacts between the Sarykamysh Ossetians and their historical homeland during the period of Russian rule. From other types of oral creativity, legends and parables “from Caucasian life” (including about the Caucasian war and Shamil), as well as samples of Anatolian folklore, were noted.

Ossetian and other Caucasian dances were well preserved and regularly performed on solemn occasions. The only musical instrument was the harmonica.

The attention of the Turkish researcher was attracted by the high age of marriage in Ossetian villages (for men, often over 30 years), which was associated not only with economic problems, but also with the difficulty of choosing a marriage partner within one's own ethnic group due to its small number. The latter circumstance, long before the time described, led to the lifting of the ban on marriages between representatives of different traditional social status strata (“noble” and “ignoble” surnames), as well as members of related (Rwadal) surnames. There were precedents for cross-cousin marriage, but public opinion condemned them. The payment of kalym in the amount of 150 Turkish liras (the approximate cost of two horses) was obligatory. An indispensable condition for concluding a marriage was the voluntary consent of both young people. Bride kidnapping was frowned upon and was quite rare. In general terms, the wedding ritual described by Kazmaz as a whole differs little from typical samples of the Ossetian wedding. Traditional forms of intrafamilial avoidance were practiced, although they were no longer enforced as strictly as in the earlier period.

Labor education of children began at a very early age. In addition to purely household skills, much attention was paid to teaching boys the art of riding (although this tradition has already begun to lose its significance), and girls - needlework, in which they had no equal in neighboring villages. A distinctive feature of the Ossetians was the desire of parents to provide their children with a modern education; there were almost no children not attending primary or secondary school, despite the fact that not all villages had schools.

Compared with the neighboring population, women in the Ossetian villages enjoyed considerable freedom (they did not avoid men, did not wear a veil, etc.). The norm of men's behavior was emphatically respectful attitude towards women. The duty of women in the family was housekeeping, but they, as a rule, did not do field work.

The respectful attitude towards elders also remained the norm of behavioral etiquette, but their real influence in public life was steadily weakening. survived at least until the early 1920s. the institution of the mediative court of elders ceased to exist by the indicated time. Increasingly, disagreements between generations on socio-economic and cultural issues made themselves felt.

Funeral customs combined Ossetian and Islamic traditions, but the level of honors given to the dead was noticeably higher than in neo-Ossetian villages.

By the nature of their religious consciousness, the Sarykamysh Ossetians were completely orthodox Sunni Muslims who sought to follow the precepts of Islam in their daily lives. The villagers, as far as can be judged from this text, for the most part observed the fast, but performed prayer very irregularly. Veiling by women was not noted. In most villages there was a mosque, as well as a mullah or muezzin, but, as a rule, from non-local residents. Pilgrimage was practiced to the graves of Muslim saints located in the area - ziyarets. There were no signs of the existence of remnants of traditional (pre-Muslim) cults.

The material of Kazmaz indicates that the Sarykamysh Ossetians in the middle of the 20th century. retained the most important socio-cultural features inherited from the maternal ethnic group. Their group identity was based primarily on a clear awareness of their common origin and their social and cultural “specialness” in a given region. The situation in other Ossetian communities, apparently, did not fundamentally differ from the one described, except for a slightly greater adherence to Islamic norms and traditions of the Ossetians in a number of areas of Central Anatolia (especially the province of Yozgat) due to their residence among the relatively conservative Turkish population.

This conclusion is fully supported by the material of another field study (unfortunately, very fragmentary), undertaken among the Sarykamysh Ossetians around the same period by the Turkish ethnologist Yashar Kalafat. One can also refer to the valuable observations of the life and way of life of Turkish Ossetians by the well-known journalist M. Mamsurov, made by him during his trip to Turkey in 1971.

This situation generally persisted until the 1960s and 1970s, when, due to the acceleration of the industrial development of Turkey and the processes of internal migration and urbanization caused by it, there were cardinal changes in the structure of the settlement of the Ossetian and other Caucasian populations. Since that time, almost all Ossetian villages and micro-enclaves began to undergo a gradual “erosion” due to the growing emigration of the economically active part of the inhabitants from them to the large commercial and industrial centers of the country, which in many cases was accompanied by an influx of Turkish and Kurdish ethnic elements from the outside into the villages left by the Ossetians. The destruction of the original settlement structure of the Ossetian communities took on a particularly intense and irreversible character in the last decades of the 20th century, marked by a complete exodus from the countryside of the Ossetian population of Eastern Anatolia and an almost complete exodus of Central Anatolia. As a result, at present, the only Ossetian island in Turkey are two villages in the province of Yozgat - Poyrazly and Boyalyk (the first is Digor, the second is Iron), which generally retain their mono-ethnic status with a population of several hundred people. Thus, in a fairly short period of time, Turkish Ossetians, whose total number was estimated at about 20-25 thousand people by the beginning of the 21st century, turned from a predominantly agrarian, to a certain extent patriarchal community into an almost completely urbanized one. The vast majority of its members are concentrated in rapidly developing cities remote from the areas of their former settlement (primarily in the Istanbul metropolis, as well as in Ankara, Izmir, Bursa, Antalya, etc.), some live in Anatolian provincial cities (Yozgat, Tokat, Sivas, Kayseri, Erzurum, Kars, etc.), and only a small number - in the villages. Moving to large cities, where the Ossetians settled very scattered and managed to quickly integrate into the dominant Turkish society (usually as employees, military men, entrepreneurs and freelancers), on the one hand, gave a strong impetus to the processes of their cultural and linguistic assimilation. So, today, almost none of the people born and raised outside the "old" Ossetian villages (that is, people of young and partly middle age) speak their native language. On the other hand, with the inclusion in the modern urban environment, the formation of the intellectual, business, bureaucratic and other elite of the Ossetian diaspora has accelerated, some of which is quite actively involved in the Ossetian and wider North Caucasian ethnocultural and social movement in Turkey.

However, despite the growing linguistic assimilation and acting in the country since the 30s. the law on the obligatory wearing of Turkish surnames, today almost all Turkish Ossetians remember their original family names well and use them in informal communication with each other. According to the incomplete data of the late professor V.S. Uarziati, one of the few domestic scientists who devoted special works to the Middle Eastern Ossetians, representatives of the following Ossetian surnames live in Turkey and Syria: Aguydz (ar) tæ, Abysaltæ, Atsætæ, Asetæ, Ælbegtæ, Æmbaltæ, Ærch'egkatæ, Ballatæ, Babukatæ, Baskatæ, Bastæ , Batiato, Batyrtæ, Badtæ, Baluit, Bærojtæ, Belekkatæ, Barrozt, Brootæ, Biazyrtæ, Bimbasate, Bzartæ, Boltæ, Bourge, Pooletæ, Gadotæ, Newspapers, Gæbæratæ, Gaguytæ, Galiotæ, Gamaztæ, Gazatzatæ, Gasoytæ, Gægcatæ , Dzanægatæ, Dzansohtæ, Dzapartæ, Dzaras(a)tæ, Dzgoitæ, Dzustæ, Dzuzzatæ, Dzykhhotæ, Dogætæ, Yesenatæ, Zakkutæ, Zaqyetæ, Zekhyetæ, Zoloitæ, Itazatæ, Kaditæ, Karsan(a)tæ , Kodzatæ, Kuyundyatæ, Keziatæ, Kaabolatæ, Kuænguratæ, Leuantæ, Lian (a) Tæ, Makuaratæ, Mamsaratæ, Makhyotæ, Mildzõhtæ, Murzatæ, Merkatæ, Musalatæ, Nækuatæ, Nogatæ, Pohatæ, Rubytæ, Salitæ, Sambgtæ, Sasiatæ, SalitхTheatæ , Elephantæ, Sikh'otæ, Tauh'azakhtæ, Taysautæ, Tautiatæ, Tezi (a) tæ, Temyrhantæ, Timortæ, Tugantæ, Tuhastatæ, Fidaratæ, Hekelatæ, Hositæ, Hosontæ, Habantæ, Hantemurtæ, Hanyhuatæ, Hæbælotæ, Hæræbugatæ, Hæmmærzatæ, Hodzatæ, Hotsharatæ, Huybadtæ, Huysatæ, Tsælykkatæ, Tsomartatæ, Tsoritæ, Tsærikatæ, Tsækhiltæ, Chedzhemtæ. It is curious that some of these surnames are currently unknown in Ossetia itself.

Created by representatives of this elite in 1989 in Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Mutual Aid "Alan" aims to "ensure the social solidarity of the Ossetians living in Turkey ... and the protection and development of their cultural values" . The Foundation organizes regular meetings of people from Ossetian villages, provides material assistance to needy compatriots in obtaining education, treatment, etc., creates courses on the study of the Ossetian language and national musical and choreographic art, publishes translations into Turkish of scientific and popular science history and culture of the Ossetian people, etc. An important activity of the foundation is the establishment and maintenance of contacts with the historical homeland through official institutions, public organizations, educational institutions, family ties, etc. Immediately after the events of August 2008 in South Ossetia, with the active participation of the activists of the Alan Foundation and other Caucasian associations of Turkey, the “Caucasian-Ossetian Committee of Solidarity and Humanitarian Aid” was created, which played a very important role in holding large-scale actions in Turkish cities in support of the victims of armed aggression of the South Ossetian Republic, lobbying its interests in the political and mass media circles of the country, raising funds for the affected brethren, etc.

Thus, at the current stage, it is legitimate to talk about the presence in Turkey of a fairly close-knit community with a developed diaspora ethnic identity (along with the Turkish national-state identity) and certain mechanisms of self-organization of the community of descendants of the Ossetian Muhajirs of the 19th century. At the same time, it is obvious that this ethno-protective and cultural-educational activity, in which an absolute minority of Turkish Ossetians are involved on any permanent basis, cannot form a reliable barrier to the prevailing trend towards their further de-ethnization. Because of this, the final assimilation of this part of the Ossetian ethnos still seems to be a matter of time, although the intensity and pace of this process can be significantly influenced by such factors as the scale and quality of the democratic changes taking place in Turkey today, the level and nature of the diaspora’s ties with Ossetia, and also the general regional international political context.

As for the Ossetians, who ended up within Syria after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, their history in the 20th century also saw radical changes inseparable from the fate of the entire North Caucasian community of the Golan Heights. Having managed to secure a fairly high socio-political status for themselves during the period of the French mandate, the Circassians of the Quneitra region after the declaration of the independent Syrian Republic were forced to put up with a significant restriction of their ethno-cultural rights, despite the fact that they continued to be very widely represented at all levels of official civil and power structures. Fatal for this minority was 1967, when, as a result of the Six-Day War with Israel, Syria lost control over the Golan, and the inhabitants of the Caucasian villages located here, including Ossetians, fled from their homes into the interior of the country. After that, the main part of the Ossetians settled in Damascus and some other cities of Syria, where their number today hardly exceeds 1 thousand people, and the language and ethno-cultural characteristics are increasingly being assimilated by the dominant Arab society. A small number of Ossetian and other refugees emigrated to the United States after these events. Most of them now live in the town of Patterson, New Jersey, where one of the most significant North Caucasian communities in the Americas was formed in the post-war decades.

LITERATURE:

1. Scientific archive of the North Ossetian Institute for Humanitarian and Social Research. IN AND. Abaev. Fund 13.

2. Basbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi. Sadaret. Mektubi Kalemi. Meclis-i Vala.

3. Basbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi. Sadaret. Mektubi Kalemi. Nezaret ve Devair.

4. Basbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi. Babıali Evrak Odası. Muhacirin Komisyonu.

5. Alborov B.A. The first Ossetian poet Temirbolat Osmanovich Mamsurov // Proceedings of the Gorsky Pedagogical Institute. T. III. Vladikavkaz, 1926.

6. Bakradze D.Z. Historical and ethnographic sketch of the Kars region // Izvestiya of the Caucasian Department of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. T. VII. No. 1. Tiflis, 1881.

7. Kanukov I.D. In the Ossetian village. Stories, essays, journalism. Ordzhonikidze, 1985.

8. Kolyubakin A.M. Materials for military-statistical review of Asiatic Turkey. T. I. Part I. Tiflis, 1888.

9. Kundukhov M. Memoirs of General Mussa Pasha Kundukhov // "Daryal". Vladikavkaz, 1994. No. 4; 1995. #1–3.

10. Mamsyraty M. Ætsægælon bæstæ. Ordzhonikidze, 1986.

11. Ossetia in the Caucasian policy of the Russian Empire (XIX century). Collection of documents and materials / Ed. A.A. Khamitsaeva. Vladikavkaz, 2008.

12. The first general census of the population of the Russian Empire, 1897, Vol. LXIV. Kars region. SPb., 1904.

13. The resettlement of the highlanders in Turkey. Materials on the history of mountain peoples / Comp. G.A. Dzagurov. Rostov-on-Don, 1925.

14. Totoev M.S. On the issue of the resettlement of Ossetians in Turkey // Proceedings of the North Ossetian Research Institute. T. XIII. Issue. I. Dzaudzhikau, 1948.

15. Ouarziates V.S. Iron mukhadzyrtæ Turchy // "Mach of arcs". Dzudzhykhzhu, 1992. No. 3.

16. Helmitsky P. Kars region. Military Statistical and Geographical Review. Part II. Dep. 2–3. Tiflis, 1893.

17. Hotko S.Kh. Alans and Asses in Mamluk Egypt // Daryal. Vladikavkaz, 1995. No. 1.

18. Chochiev G.V. Settlement of North Caucasian immigrants in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire (2nd half of the 19th - early 20th centuries) // Ottoman Empire: country and people. M., 2000.

19. Chochiev G.V. Information of the Turkish ethnographer J. Kalafat about the folk beliefs of the Sarykamysh Ossetians // News of the North Ossetian Institute for Humanitarian and Social Research. Issue. 1(40). Vladikavkaz, 2007.

20. Atılgan Z. Muş, Bitlis ve Bingöl İllerindeki Kuzey Kafkasyalı Muhacirler // "Birleşik Kafkasya" . İstanbul, 1965. No. 5.

21. Aydemir İ. Türkiye Çerkesleri // "Kafkasya". Ankara, 1973–75. Nos. 36–47.

22. Burnaby F. On Horseback through Asia Minor. Vol. I–II. L., 1878.

23. Correspondence relating to the Asiatic Provinces of Turkey, 1894–95. Presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty // "Turkey" . L., 1896. No. 6.

24. Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey. Ed. by P.A. Andrews. Wiesbaden, 1989.

25. Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey. Supplement and Index. Ed. by P.A. Andrews. Wiesbaden, 2002.

26. Fırat M.Ş. Dogu İlleri ve Varto Tarihi. Ankara, 1981.

27. Gazi Ahmed Muhtar Pasa. AnIlar. C.II. Sergüzeşt-i Hayatım'ın Cild-i Sanisi. Istanbul, 1996.

28. Kazmaz S. Sarıkamış'ta Köy Gezileri. Ankara, 1995.

29. Kubat T. Muhacirin Hicrandır Ömrünün Yarısı. Ankara, 2005.

30. Lynch H.F.B. Armenia: Travels and Studies. Vol. II. The Turkish Provinces. L., 1901.

Introduction

Ossetians are the descendants of the ancient Alans, Sarmatians and Scythians. However, according to a number of well-known historians, the presence of the so-called local Caucasian substratum in the Ossetians is also obvious. At present, Ossetians mostly inhabit the northern and southern slopes of the central part of the main Caucasian ridge. Geographically, they form the Republic of North Ossetia - Alania (area - about 8 thousand square kilometers, the capital - Vladikavkaz) and the Republic of South Ossetia (area - 3.4 thousand square kilometers, the capital - Tskhinval).

Throughout its history, the Ossetian people went through periods from rapid prosperity, strengthening of power and huge influence in the first millennium of our era, to almost complete catastrophic extermination during the invasions of the Tatar-Mongol and lame Timur in the XIII-XIV centuries. The comprehensive catastrophe that befell Alania led to the mass destruction of the population, undermining the foundations of the economy, and the collapse of statehood. The miserable remnants of the once powerful people (according to some sources, no more than 10-12 thousand people) were locked up in the high mountain gorges of the Caucasus Mountains for almost five centuries. During this time, all "external relations" of the Ossetians were reduced only to contacts with the closest neighbors. However, there is no evil without good. According to scientists, largely due to this isolation, the Ossetians have preserved their unique culture, language, traditions and religion almost in their original form.

Ossetian culture tradition education

Migration from the mountains to the plains. Territory and population

.Resettlement of Ossetians to the plain

The resettlement of the highlanders-Ossetians was carried out according to a predetermined plan. The plan was approved by A.P. Yermolov, the commander-in-chief of the Russian army in the Caucasus. According to the adopted plan, the Ossetians, who lived on the northern slopes of the Caucasus Range, moved to the foothill plains. The Tagauri society was assigned lands between the Terek and Mayramadag, the Kurtatinsky society - between Mayramadag and Ardon, the Alagir society - the Ardon-Kurp interfluve. The lands provided to the Digor society were divided between feudal families and were located in the western regions of Ossetia along the basins of the Durdur, Urukh and Ursdon rivers. Even before the mass resettlement of North Ossetians, the right bank of the Terek was given into the possession of the Dudarovs, influential Tagauri feudal lords who controlled the passages along the Georgian Military Highway.

With the resettlement of Ossetians to the plain, A.P. Ermolov connected, first of all, the solution of problems related to the security of the Georgian Military Highway. According to his plan, the transfer of this road from the right bank of the Terek to the left and the resettlement of Ossetians on both sides of the river were to secure the road from the raids of the highlanders.

A new stage of resettlement of Ossetians began at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries. However, it took on a mass character only in the 1920s. 19th century Along with the Russian administration, the resettlement process now has its own "organizers" nominated from their own midst. Often they were people from wealthy strata of society. The local "organizers" of the resettlement cared, first of all, about observing their own class interests: they sought to become "first settlers", "founders" of new settlements, hoping that new villages would be named after them. On this basis, the Ossetian social leaders could subsequently consider the developed lands their property, and the inhabitants of the settlements - dependent. Such villages, as a rule, had family names: for example, the villages of the Kozyrevs, Yesenovs, Mamsurovs, Kundukhovs, Dzhantievs, and others.

New settlements were still founded near Russian military fortifications, such as Vladikavkaz, Ardon, Arkhon, Upper Dzhulat and others. Such close proximity was typical only for Ossetian settlers, they even created settlements mixed with Russian fortifications. This was explained not only by the fact that the Ciscaucasian plain remained a turbulent place, but also by the openness of the people themselves, their inclination to economic and cultural cooperation.

The wave of mass resettlement of Ossetians, which began in the 1920s, subsided somewhat by the end of the first quarter of the 19th century. This process was suspended by the frequent raids on Ossetian settlements by the Kabardian feudal lords and the Ingush. The Caucasian War, which began in 1823, which complicated the military-political situation in the North Caucasus, also influenced the rate of migration of mountaineers to the plain. By 1830, due to the military events in the Caucasus, as well as the actions of the Russian government aimed at tightening the colonial regime, the resettlement of Ossetians to the plain was completely suspended. There was also an internal reason for its termination. Resettlement from the mountains to the plains could not but have its natural limits, beyond which the destruction of the organization of Ossetian society that took shape over the centuries began. The people felt that resettlement to a new geographical habitat and the abandonment of familiar mountain conditions, along with the blessing, fraught with the danger of losing internal social and traditional integrity, which, in turn, could plunge Ossetian society into a state of deep depression.

The Russian administration, of course, noticed that the raids posed a significant external danger for the Ossetians, which could cause them to refuse to move from the mountains to the plains. But she did not seek to delve into the more complex aspects of this problem. In pursuing their own military-political goals, since 1830 the Russian administration began violent methods of evicting Ossetians from the mountains. First of all, they were evicted from those places where military communications passed, hoping in this way to secure the actions of their troops in the most difficult areas for them. As a result of such a policy of the Russian government, the resettlement of the inhabitants of the mountainous regions took on the character of deportation. Not only Ossetian villages were deported, but, at times, entire regions, such as, for example, the mountain basin of the Terek River, where the Georgian Military Highway ran and where Ossetian villages were compactly located.

Soon, however, the Russian administration, having met resistance from Ossetia, abandoned violent methods, and resettlement again began to take place on the principle of voluntariness.

The Georgian state had long-standing ties with the Ossetians living in the North Caucasus. These ties were either friendly or hostile. Like their ancestors - the Alans, the Ossetians did not have a permanent place of residence for a long historical period; before settling in the mountains of the Caucasus, they changed their habitat several times. Their ancestors, Iranian-speaking tribes, came from the Central Asian steppes. At the turn of our era, the Alans-Ossetians settled in the Azov steppes and on the banks of the Don, where in the 4th century AD. subjected to devastating attacks by the Huns.

A small part of the Alans that survived these attacks heads south and settles in the foothill steppes of the North Caucasus. On this territory, the Alans-Ossetians founded an early class state formation, which was subsequently destroyed by the Mongols (XIII century). XIII-XIV centuries were marked by a new resettlement of the Alan-Ossetians. Settling in the lands of the North Caucasus, they mix with the North Caucasian tribes, and the early settlements of the Ossetians in the North Caucasus are occupied by the Kabardians, having built reliable fortifications on the foothills. This was intended to detain the Ossetians driven into the mountains and isolate them from the flat regions of the North Caucasus.

Until the 13th-14th centuries, Ossetians did not live in the so-called mountains at all. North Ossetia. (In fairness, it must be said that from the early Middle Ages, the Alans lived in the upper reaches of the Kuban River, on the territory of today's Karachay; here they coexisted with the Abkhazians. This is confirmed by the fact that the inhabitants of Western Georgia call the Karachays "Alans"). Only after the 14th century did they become direct neighbors of the Georgians. Ossetians - the inhabitants of the plains are turning into highlanders. Their settlement of mountainous regions was massive, which was reflected in toponyms brought from the plain to the mountains.

The final expulsion of the Ossetians into the mountain gorges occurred as a result of two crushing raids by Tamerlane at the beginning of the 15th century.

The thesis about the ancient settlement of Ossetians on the territory of Georgia is devoid of any basis whatsoever. Not a single historical source, document or archaeological fact testifies to the migration of Ossetians to Georgia before our era, as well as in the 4th century AD. The invasion of the Huns did not entail the resettlement of the Alan-Ossetians to Georgia. During this period, they migrated from the steppes of the Don and Azov regions relatively to the south, to the foothill steppes of the North Caucasus.

Contrary to the opinion of some authors, no settlement of Ossetians in Georgia can be traced either in the 7th or in the 13th century. In the XIII century, Ossetians begin to settle only in the mountain gorges of the North Caucasus. This migration process was relatively long and ended at the beginning of the 15th century. In this period of time, only a small group of Ossetians tried to settle in Shida Kartli. Using the weakening of Georgia and the support of the Mongols, whose police detachments they actually made up, the Ossetians are trying to seize the lands of Shida Kartli. However, they were expelled and destroyed by Tsar George Brtskinvale (the Brilliant). Thus, the Georgian authorities closed the gates leading from Ossetia to Georgia (Darial and Kasris Kari) for a long time.

Ossetian settlement began in the 15th century in the Georgian province of Dvaleti, located in the north of the Main Caucasian Range. This process was carried out mainly during the 16th century, and in the 17th century in Dvaleti the assimilation of the local Georgian Dval tribe by Ossetians ends. It should be noted that a significant part of the Dvals, oppressed by the Ossetians, before their settlement in Dvaleti migrated to various parts of Georgia (Shida Kartli, Kvemo Kartli, Imereti, Racha). The remaining Dvals found themselves in the ethnic-linguistic environment of the Ossetians, and as a result of the mass settlement of the region by the latter and their rapid reproduction, they were assimilated. Despite the ethnic changes, this province was not separated from Georgia. Throughout the history of Georgian statehood, as well as after its transformation into a Russian colony (until 1858), Dvaleti was an integral part of Georgia.

The first Ossetian settlements on the territory of present-day Georgia appear in the Truso gorge (at the source of the Terek river) and in Magran-Dvaleti (at the source of the Didi Liakhvi river). Ossetians migrated to these places from the North Caucasian gorges in the middle of the 17th century. By that time, the Ossetians had not yet mastered a significant part of the mountainous Shida Kartli. They lived only in the upper Didi Liakhvi (Magran-Dvaleti). According to a number of historical sources, at that time the mountainous part of Shida Kartli (Didi and Patara Liakhvi gorges) was dotted with devastated villages. Driven from these places and forced to leave them, the Georgian population moved to the plain and settled there.

Since the second half of the 17th century, Ossetians have been migrating to the mountainous part of Shida Kartli, namely, to the upper reaches of the rivers Didi and Patara Liakhvi; they gradually move to the south, and by the 30s of the 18th century they completely master the mountainous zone of the gorges of the mentioned rivers. During this period, in some mountain villages, Ossetians coexist with the small Georgian population remaining there.

Throughout the 18th century, Ossetian settlements in the foothills of Shida Kartli were not attested. Their development of this territory (mainly devastated villages) occurs from the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries. By the beginning of the 18th century, Ossetians settled in the sources of the Dzhejori (Kurado) and in the Ksani Gorge (Zhamuri). In Jamuri, they migrate both from the mountain gorges of the North Caucasus and from the mountain zone of the Didi Liakhvi gorge, while in Kudaro, mainly from Dvaleti. In the mountainous Shida Kartli, Ossetians first settled in the Didi Liakhvi gorge, and then in the Patara Liakhvi gorge, at the sources of the Ksani (Zhamuri). At the beginning of the 18th century, a small Ossetian population appeared in Isroliskhevi, as well as in the upper part of the Mejuda gorge, where Ossetians rushed, who previously lived in the Patara Liakhvi gorge.

By the end of the 18th century, the extreme points of the Ossetian settlements (in the direction from west to east) were Kudaro (at the source of the Dzhedzhori river) - Gupta (Didi Liakhvi gorge) - the area above the village of Atserishevi (in the Patara Liakhvi gorge) - two villages in the Mejuda gorge - Zhamuri (in the Ksani gorge) - Guda (at the source of the Tetri Aragvi) - Truso (at the source of the Terek river). By the end of the 18th century, in the gorges of Lekhura, Mejud (with the exception of its beginning), in most of the mountainous part of the Ksani gorge and in the Prone gorges, the presence of Ossetians was not at all confirmed. Consequently, both in the time of Vakhushti Bagrationi and by the end of the 18th century, Ossetians lived only in mountainous areas, devoid of “grape and fruit” plantations.

By the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, Ossetians settled a significant area of the foothills in the Patara Liakhvi gorge. Since that time, and especially in the first years of the 19th century, there has been an individual migration ("leakage") of Ossetians from the mountainous regions of Shida Kartli to the foothills and plains of this region. Ossetians moved most often from the Patara Liakhvi gorge. Since the end of the 18th century, the migration of Ossetians from the mountain gorges of the North Caucasus to Georgia has actually stopped. This was due to the permission of the official government of Russia for the resettlement of Ossetians in the foothills of the plains of the North Caucasus. The only exception was the Ossetian population of Dvaleti, who continued to migrate to the territory of Georgia throughout the 19th century. Settlement was carried out mainly through Dvaleti. The Ossetians who settled there, who came from the North Caucasian mountain gorges, after some time moved to Shida Kartli. However, the facts of the direct migration of Ossetians there from the North Caucasian mountainous corners were also confirmed, which was typical mainly for the early, initial stage of the resettlement of the Ossetian population.

The statements of some authors about the Ossetians living in the foothills of Shida Kartli and on the plain in the 17th-18th centuries seem unreliable. At the beginning of the 19th century, their migration began to the gorges of the Prone, Mejuda, Lekhura rivers, as well as to other settlements of the Ksani gorge. Ossetians settled ancient Georgian villages in the Prone gorges mainly from the gorge of the Didi Liakhvi River. However, noteworthy is the fact that the first Ossetian migrants in the Georgian villages of the Prone Gorges came from Dvaleti. From the gorges of the Didi and Patara Liakhvi rivers, the population moves to the Mejud gorge. Ossetian migration to the Lekhura gorge was carried out mainly from the Ksani gorge (Zhamuri, Churta). However, in the first quarter of the 19th century, in the gorges of Lekhura, Mejuda and Prone, the settlement of Ossetians was not intense; such a process began mainly in the middle of the 19th century and lasted until the 1880s.

Since the 30s of the 19th century, isolated Ossetian families appeared on the territory located on the right bank of the Kura River (Gagmamkhari) in Shida Kartli, and Ossetians mainly migrated to this region in the second half of the 19th century. At this time, Ossetians inhabit the present Borjomi region (Gujareti gorge). Ossetians moved to Kakheti and Kvemo Kartli from the mountainous Shida Kartli at the beginning of the 20th century.

It cannot be said that the arrival and resettlement of Ossetians on the territory of Georgia had a peaceful character. Pressed in the mountain gorges of the North Caucasus, the Ossetians by force cleared their way both to Dvaleti and to the mountainous part of Shida Kartli. According to historical documents, the Georgian population of local villages, exhausted by Ossetian raids, left the inhabited mountainous places of their ancestors and moved to the plain, where circumstances were favorable for them: due to the constant raids of enemies, the foothills of Shida Kartli, as well as the plain regions, faced a real threat of a demographic catastrophe.

The migration of Ossetians to Dvaleti and the mountainous Shida Kartli, in a sense, was facilitated by the socio-political situation of Georgia at that time. Fragmented as a result of frequent enemy attacks, Georgia could not exercise control over the main gates leading from the North Caucasus to our country - Darialom and Kasris Kari.

In the subsequent period (XVIII century) the country's economic situation deteriorated sharply, the demographic situation in Shida Kartli became the most difficult, and the Georgian rulers (king, princes) themselves often contributed to the resettlement of Ossetians to Georgia. In the second half of the 18th century, in the mountainous Shida Kartli, and in the first half of the 19th century, in none of the villages in the foothills of this region, the facts of residence of more than one generation of Ossetians were attested. Having lived for a short time in a mountain or foothill village, the Ossetians rushed to the south; this is confirmed by the materials of the population inventory in the 19th century. The Ossetians who settled in the foothill villages at the beginning of the 19th century were increasingly moving to the plains by the middle of the same century. Thus, their gradual, intensive advancement from the end of the 18th century and throughout the entire 19th century from the high-mountain Georgian villages towards the plain is beyond doubt, which was reflected in the term chamotsol "hanging", "hanging" common in Georgian historiography. The Ossetians were particularly mobile: having settled in the lowland villages in the second half of the 19th century, they immediately moved to other lowland settlements.

The social status of the Ossetians who settled in Shida Kartli is not in favor of their long stay in this region. According to the descriptions of the population of the 19th century, most of the Ossetians of the Didi Liakhvi gorge had the status of Khizans (villages driven from their former habitats and found shelter elsewhere). Part of the Khizan Ossetians, who migrated to the mountainous Shida Kartli, passed into the serfdom of the Machabeli princes, while another part retained the status of Khizan. Khizanism was mainly preserved by Ossetian migrants who came from the North Caucasus in a relatively late period (in the second half of the 18th century).

The view of the long-term relationship between Ossetia and Georgia (Ossetians and Georgians) is based on unrealistic historical facts; it requires a thorough revision and deep study. For example, the statements of some Ossetian authors about the presence in Georgia in the second half of the 18th century of 6,000 to 7,000 Ossetian smokes are erroneous, which is an artificial overestimation of the real number of the population of Ossetian nationality. The reality is this: by the end of the 18th century, 2,130 smokes (up to 15,000 souls) of Ossetians lived on the territory of modern Georgia.

Dvaleti is the first place of residence of Ossetians in the historical territory of Georgia. The question of the settlement and ethnicity of the Dvals deserves special consideration. The territory occupied by the Dvals is a mountain range similar to Pkhovi, Tusheti, Khada, Tskhavati, Gudamakari, Tskhrazma... Dvaleti was located on the northern slopes of the Main Caucasian Range, but the watershed range was much lower than the mountain range located north of Dvaleti. Eleven passes ensured a year-round connection between Dvaleti and the rest of Georgia (Shida Kartli, Racha). As for the connection of Dvaleti with the North Caucasus, only one crossing was involved here - Kasris Kari, and even then only in the summer.

Dvaleti was actively included in the system of Georgian statehood, both politically and economically, as well as culturally and religiously. Georgia lost Dvaleti only in 1858, due to the subjugation of the metropolis of the Terek region, which was under the jurisdiction of Russia.

An incorrect interpretation of historical sources and documents caused the naming of the mountainous part of Shida Kartli (gorges of the rivers Didi and Patara Liakhvi, Ksani and Terek) as the territory of Dvaleti. In the mountainous Shida Kartli, namely, at the source of the Didi Liakhvi River, there was only the Magran-Dvaleti region, uniting nine mountain villages. It was formed relatively later (after the 10th-11th centuries), as a result of the resettlement of the Dvals from Dvaleti.

Dvaleti is the first region on the territory of Georgia that suffered devastating raids by Ossetians from the mountains of the North Caucasus, which forced the Dvalians to migrate to various parts of Georgia (Shida and Kvemo Kartli, Racha, Imereti). The first penetration of Ossetians into Dvaleti occurred at the end of the 15th century; migration was carried out mainly from the North Caucasian Alagir Gorge during the 16th-17th centuries. In the linguistic and ethnic environment of the Ossetian migrants, the Ossetianization of the Dvals remaining in place took place. This process was progressive and spanned several generations. At the end of the 17th century, the Ossetianization of the Dvals was already completed, but even in the first quarter of the 18th century, one part of them still retains its original features. Following the historical tradition, Ossetian newcomers begin to call themselves Dvals.