PART 1

“At the beginning of July, in an extremely hot time, in the evening, one young man came out of his closet, which he had rented from tenants in the S-th lane, onto the street and slowly, as if in indecision, went to the K-n bridge.”

He avoids meeting with his landlady because he has a large debt. “It’s not that he’s so cowardly and downtrodden... but for some time he was in an irritable and tense state, similar to hypochondria... He was crushed by poverty.” A young man is thinking about some task he has planned (“Am I capable of this?”). “He was remarkably good-looking, with beautiful dark eyes, dark-haired, taller than average, thin and slender,” but he was so poorly dressed that another person would be ashamed to go out into the street in such rags. He’s going to “do a test run for his enterprise,” and that’s why he’s worried. He approaches a house that “stood entirely in small apartments and was inhabited by all sorts of industrialists.” As he climbs the stairs, he experiences fear and thinks about how he would feel “if he really somehow happened to get to the point.”

He calls and is answered by “a tiny, dry old woman, about sixty years old, with sharp and angry eyes, a small pointed nose and bare hair. Her blond, slightly gray hair was greased with oil. Around her thin and long neck, similar to a chicken leg, there was some kind of flannel rag wrapped around her, and on her shoulders, despite the heat, a disheveled and yellowed fur coat was hanging. The young man reminds him that he is Raskolnikov, a student who came a month earlier. He enters a room furnished with old furniture, but clean, says that he has brought a mortgage, and shows an old flat silver watch, promises to bring another little thing one of these days, takes the money and leaves.

Raskolnikov torments himself with thoughts that what he has planned is “dirty, dirty, disgusting.” In the tavern he drinks beer, and his doubts dissipate.

Raskolnikov usually avoided society, but in a tavern he talks with a man “over fifty years old, of average height and heavy build, with gray hair and a large bald spot, with a yellow, even greenish face swollen from constant drunkenness and with swollen eyelids, due to which Tiny eyes were shining.” It “had both sense and intelligence.” He introduces himself to Raskolnikov like this: “I am a titular adviser, Marmeladov.” He responds by saying that he is studying. Marmeladov tells him that “poverty is not a vice, it is the truth”: “I know that drunkenness is not a virtue, and this is even more so.

But poverty, dear sir, poverty is a vice. In poverty you still retain your nobility of innate feelings, but in poverty no one ever does. For poverty they are not even kicked out with a stick, but swept out of human company with a broom, so that it would be all the more offensive; and rightly so, for in poverty I am the first to be ready to insult myself.” He talks about his wife, whose name is Katerina Ivanovna. She is “a lady, although generous, but unfair.” She ran away with her first husband, who was an officer, without receiving parental blessing. Her husband beat her and loved to play cards. She gave birth to three children. When her husband died, Katerina Ivanovna, out of despair, remarried Marmeladov.

She is constantly at work, but “with a weak chest and inclined toward consumption.” Marmeladov was an official, but then lost his position. He was also married and has a daughter, Sonya. In order to somehow support herself and her family, Sonya was forced to go to the panel. She lives in the apartment of the tailor Kapernaumov, whose family is “tongue-tied.” Marmeladov stole the key to the chest from his wife and took the money, with which he drank for the sixth day in a row. He visited Sonya, “he went to ask for a hangover,” and she gave him thirty kopecks, “the last, all that was.” Rodion Raskolnikov takes him home, where he meets Katerina Ivanovna. She was “a terribly thin woman, thin, rather tall and slender, with beautiful dark brown hair...

Her eyes shone as if in a fever, but her gaze was sharp and motionless, and this consumptive and agitated face made a painful impression.” Her children were in the room: a girl of about six was sitting and sleeping on the floor, a boy was crying in the corner, and a thin girl of about nine was comforting him. There is a scandal over the money that Marmeladov drank away. As he leaves, Raskolnikov takes from his pocket “how much copper money he got from the ruble exchanged in the tavern,” and leaves it on the window. On the way, Raskolnikov thinks: “Oh, Sonya! What a well, however, they managed to dig! and use it!”

In the morning, Raskolnikov examines his closet “with hatred.” “It was a tiny cell, about six paces long, which had the most pitiful appearance with its yellow, dusty wallpaper falling off the wall everywhere, and so low that even a slightly tall person felt terrified in it, and everything seemed to be... you'll hit your head on the ceiling. The furniture matched the space.” The hostess has already “stopped giving him food for two weeks.” The cook Nastasya brings tea and says that the hostess wants to report him to the police. The girl also brings a letter from her mother. Raskolnikov is reading. His mother asks him for forgiveness for not being able to send money.

He learns that his sister, Dunya, who worked as a governess for the Svidrigailovs, has been at home for a month and a half. As it turned out, Svidrigailov, who “has long had a passion for Duna,” began to persuade the girl to have a love affair. This conversation was accidentally overheard by Svidrigailov’s wife, Marfa Petrovna, who blamed Dunya for the incident and, driving her out, spread the gossip throughout the district. For this reason, acquaintances preferred not to have any relations with the Raskolnikovs. However, Svidrigailov “came to his senses and repented” and “provided Marfa Petrovna with complete and obvious evidence of Dunya’s innocence.”

Marfa Petrovna informed her friends about this, and immediately the attitude towards the Raskolnikovs changed. This story contributed to the fact that Pyotr Petrovich Luzhin (“he is a businesslike and busy man and is in a hurry to St. Petersburg”) wooed Duna, and “she is a firm, prudent, patient and generous girl, although with an ardent heart.” There is no love between them, but Dunya “will set herself the task of making her husband’s happiness as a duty.” Luzhin wanted to marry an honest girl who had no dowry, “who had already experienced misfortune; because, as he explained, a husband should not owe anything to his wife, but it is much better if the wife considers her husband to be her benefactor.”

He is going to open a public law office in St. Petersburg. The mother hopes that in the future Luzhin will be able to be useful to Rodion, and is going to come to St. Petersburg, where Luzhin will soon marry his sister. He promises to send him thirty-five rubles.

Raskolnikov read the letter and cried. Then he lay down, but his thoughts did not give him rest. He “grabbed his hat, went out” and headed towards Vasilievsky Island through V-Prospekt. Passers-by mistook him for a drunk.

Raskolnikov realizes that his sister, in order to help him, her brother, is selling herself. He intends to prevent this marriage and is angry with Luzhin. Reasoning with himself, going over each line of the letter, Raskolnikov notes: “Luzhin’s cleanliness is the same as Sonechka’s cleanliness, and maybe even worse, nastier, meaner, because you, Dunechka, still rely on excess comfort, and there it’s simply a matter of starvation!” He cannot accept his sister's sacrifice. Raskolnikov torments himself for a long time with questions that “were not new, not sudden, but old, painful, long-standing.” He wants to sit down and is looking for a bench, but then suddenly he sees a drunken teenage girl on the boulevard, who, apparently, got drunk, was dishonored and kicked out.

She falls onto the bench. “Before him was an extremely young face, about sixteen years old, maybe even only fifteen—small, blond, pretty, but all flushed and as if swollen.” A gentleman has already been found who is trying on the girl, but Raskolnikov interferes with him. “This gentleman was about thirty years old, thick-set, fat, bloody, with pink lips and a mustache, and very smartly dressed.” Raskolnikov is angry and therefore shouts to him: “Svidrigailov, get out!” - and attacks him with fists. The policeman intervenes in the fight, listens to Raskolnikov, and then, having received money from Raskolnikov, takes the girl home in a cab. Rodion Raskolnikov, discussing what awaits this girl in the future, comes to the understanding that her fate awaits many.

He heads to his friend Razumikhin, who “was one of his former university comrades.” Raskolnikov studied intensely, did not communicate with anyone and did not take part in any events, he “seemed to be hiding something to himself.” Razumikhin, “tall, thin, always poorly shaven, black-haired,” “was an unusually cheerful and sociable guy, kind to the point of simplicity. However, underneath this simplicity there was hidden depth and dignity.” Everyone loved him. He did not attach importance to life's difficulties. “He was very poor and decidedly, alone, supported himself, earning money by doing some work.” It happened that he did not heat his room in the winter and claimed that he slept better in the cold. He was now temporarily not studying, but was in a hurry to improve his affairs in order to continue his studies. About two months ago, the friends saw each other briefly on the street, but did not bother each other with communication.

Razumikhin promised to help Raskolnikov “get lessons.” Without understanding why he is dragging himself to his friend, Raskolnikov, he decides: “After that, I’ll go, when it’s over and when everything goes anew.” And he catches himself thinking that he is thinking seriously about what he has planned, thinking about it as a task that he must complete. He goes wherever his eyes lead him. In a nervous chill, he “passed Vasilyevsky Island, went out onto the Malaya Neva, crossed the bridge and turned to the islands.” He stops and counts the money: about thirty kopecks. He calculates that he left about fifty kopecks with Marmeladov. In the tavern he drinks a glass of vodka and snacks on a pie on the street. He stops “completely exhausted” and falls asleep in the bushes before reaching home. He dreams that he, a little boy, about seven years old, is walking with his father outside the city.

Not far from the last of the city gardens stood a tavern, which always aroused fear in him, since there were many drunken and pugnacious men hanging around. Rodion and his father go to the cemetery, where the grave of his younger brother is located, past a tavern, next to which stands a “skinny Savras peasant nag” harnessed to a large cart. A drunken Mikolka comes from the tavern to the cart, and invites the noisy crowd to sit on it. The horse cannot move the cart with so many riders, and Mikolka begins to whip it.

Someone tries to stop him, and two guys whip the horse from the sides. With several blows of the crowbar, Mikolka kills the horse. Little Raskolnikov runs up “to Savraska, grabs her dead, bloody muzzle and kisses her, kisses her on the eyes, on the lips,” and then “in a frenzy, he rushes with his little fists at Mikolka.” His father takes him away. Waking up covered in sweat, Raskolnikov asks himself: is he capable of murder? Just yesterday he did a “test” and realized that he was not capable. He is ready to renounce his “damned dream” and feels free.

Heading home through Sennaya Square. He sees Lizaveta Ivanovna, the younger sister of “that same old woman Alena Ivanovna, the college registrar and pawnbroker with whom he was yesterday.” Lizaveta “was a tall, clumsy, timid and humble girl, almost an idiot, thirty-five years old, who was in complete slavery to her sister, worked for her day and night, trembled before her and even suffered beatings from her.” Raskolnikov hears that Lizaveta is being invited to visit tomorrow, so that the old woman “will be left at home alone,” and realizes that “he no longer has freedom of reason or will and that everything has suddenly been decided finally.”

There was nothing unusual in the fact that Lizaveta was invited to visit; she traded in women’s clothes, which she bought from “impoverished visiting” families, and also “took commissions, went on business and had a lot of practice, because she was very honest and always spoke extreme price."

Student Pokorev, when leaving, gave the old woman’s address to Raskolnikov, “if in case he had to pawn something.” A month and a half ago, he took there a ring that his sister gave him when they parted. At first sight, he felt an “insurmountable disgust” for the old woman and, taking two “tickets”, headed to the tavern. Entering the tavern, Raskolnikov inadvertently heard what the officer and the student were talking about among themselves about the old money-lender and about Lizaveta. According to the student, the old woman is a “nice woman”, since “you can always get money from her”: “Rich as a Jew, she can give out five thousand at once, and she doesn’t disdain a ruble mortgage.

She visited a lot of our people. Just a terrible bitch." The student says that the old woman keeps Lizaveta in “complete enslavement.” After the death of the old woman, Lizaveta should not receive anything, since everything was assigned to the monastery. The student said that without any shame in conscience he would kill and rob the “damned old woman,” because so many people disappear, and in the meantime, “a thousand good deeds and undertakings ... can be repaid with the old woman’s money.” The officer noticed that she was “unworthy to live,” but “it’s nature here,” and asked the student a question: “Will you kill the old woman yourself or not?” "Of course no! - answered the student. “I’m doing it for justice... It’s not about me here...”

Raskolnikov, worried, realizes that in his head “the same thoughts have just been born” about murder for the sake of higher justice, like those of an unfamiliar student.

Returning with Senna, Raskolnikov lies motionless for about an hour, then falls asleep. In the morning Nastasya brings him tea and soup. Raskolnikov is preparing to kill. To do this, he sews a belt loop under his coat to secure the ax, then wraps a piece of wood with a piece of iron in paper - making an imitation of a “mortgage” to distract the old woman’s attention.

Raskolnikov believes that crimes are so easily solved because “the criminal himself, and almost everyone, at the moment of the crime is subject to some kind of decline in will and reason, replaced, on the contrary, by childish phenomenal frivolity, and precisely at the moment when it is most necessary reason and caution. According to his conviction, it turned out that this eclipse of reason and decline of will engulfs a person like a disease, develops gradually and reaches its highest moment shortly before committing a crime; continue in the same form at the very moment of the crime and for some time after it, judging by the individual; then they pass, just as any disease passes.” Not finding an ax in the kitchen, Raskolnikov “was terribly shocked,” but then stole the ax from the janitor’s room.

He walks the road “sedately” so as not to arouse suspicion. He is not afraid, because his thoughts are occupied with something else: “so, it is true, those who are led to execution attach their thoughts to all the objects that they encounter on the road.”

He doesn’t meet anyone on the stairs; he notices that on the second floor in the apartment the door is open, as renovations are underway there. Having reached the door, he rings the bell. They don't open it for him. Raskolnikov listens and realizes that someone is standing behind the door. After the third ring, he hears that the constipation is being removed.

Raskolnikov frightened the old woman by pulling the door towards him, as he was afraid that she would close it. She did not pull the door towards her, but did not release the lock handle. He almost pulled the lock handle, along with the door, onto the stairs. Raskolnikov goes to the room, where he gives the old woman the prepared “pledge”. Taking advantage of the fact that the pawnbroker went to the window to look at the “mortgage” and “stood with her back to him,” Raskolnikov takes out an ax. “His hands were terribly weak; he himself heard how, with every moment, they became more and more numb and stiff. He was afraid that he would let go and drop the ax... suddenly his head seemed to spin.” He hits the old woman on the head with a gun.

“It was as if his strength was not there. But as soon as he lowered the ax once, strength was born in him.” Having made sure that the old woman is dead, he carefully takes the keys out of her pocket. When he finds himself in the bedroom, it seems to him that the old woman is still alive, and he, grabbing an ax, runs back to strike again, but sees on the neck of the murdered woman a “string” on which hang two crosses, an icon and a “small suede greasy wallet.” with a steel rim and ring." He puts the wallet in his pocket. Among the clothes he looks for gold things, but does not have time to take much. Suddenly Lizaveta appears, and Raskolnikov rushes at her with an ax. After this, fear takes over him. Every minute his disgust for what he did grows in him.

In the kitchen, he washes away traces of blood from his hands, the ax, and his boots. He sees that the door is slightly open, and therefore “locked it.” He listens and understands that someone is rising “here.” The doorbell rings, but Raskolnikov doesn’t answer. They notice behind the door that it is locked with a hook from the inside, and they suspect that something has happened. Two of those who came go downstairs to call the janitor. One remains at the door, but then also comes down. At this moment, Rodion Raskolnikov leaves the apartment, goes down the stairs and hides in the apartment where renovations are underway.

When people go up to the old pawnbroker, Raskolnikov runs from the crime scene. At home, he needs to quietly put the ax back. Since the janitor is not visible, Raskolnikov puts the ax in its original place. He returns to the room and, without undressing, throws himself onto the sofa, where he lies in oblivion. “If anyone had entered the room then, he would have immediately jumped up and screamed. Scraps and fragments of some thoughts swarmed in his head; but he couldn’t grab a single one, couldn’t stop at a single one, despite his efforts...”

PART TWO

The first thought that flashes through Raskolnikov’s mind when he wakes up is that he will “go crazy.” He's shivering. He jumps up and looks at himself at the window to check if there is any evidence, repeats the inspection three times. Seeing that the fringe on the trousers is stained with blood, he cuts it off. He hides stolen things in a hole under paper. He notices, taking off his boot, that the tip of his sock is covered in blood. After that, he checks everything several more times, but then falls on the sofa and falls asleep. He wakes up from a knock on the door. A janitor appears with a summons to the police. Raskolnikov has no idea why he is being called. He decides that they want to lure him into a trap in this way.

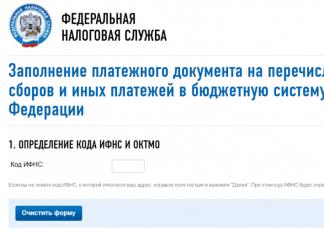

He intends to confess if he is asked about the murder. At the station, the scribe sends him to the clerk. He informs Raskolnikov that he was summoned in the case of the collection of money by the landlady. Raskolnikov explains his situation: he wanted to marry the landlady’s daughter, he spent money, issued bills; when the owner's daughter died of typhus, her mother began to demand payment of bills. “The clerk began to dictate to him the form of the usual response in such a case, that is, I cannot pay, I promise then (someday) I will not leave the city, I will not sell or give away property, and so on.”

At the police station they are talking about the murder of an old pawnbroker. Raskolnikov loses consciousness. Having come to his senses, he says that he doesn’t feel well. Once on the street, he is tormented by the thought that he is suspected.

Having made sure that his room was not searched, Raskolnikov takes the stolen things and “loads his pockets with them.” He heads to the embankment of the Catherine Canal to get rid of all this, but abandons this intention because “they might notice there.” Goes to Neva. Coming out onto the square from V-th Avenue, he notices the entrance to the courtyard, a “dead fenced-off place.” He hides the stolen things under a stone, without even looking at how much money was in the wallet, for the sake of which “he endured all the torment and deliberately went to such a vile, disgusting deed.” Everything he encounters along the way seems hateful to him.

He comes to Razumikhin, who notices that his friend is sick and delirious. Raskolnikov wants to leave, but Razumikhin stops him and offers help. Raskolnikov leaves. On the embankment, he almost gets hit by a passing carriage, for which the coachman whips him on the back. The merchant's wife gives him two kopecks because she takes him for a beggar. Raskolnikov throws a coin into the Neva.

Goes to bed at home. He's delusional. It seems to him that Ilya Petrovich is beating the landlady, and she is screaming loudly. Opening his eyes, he sees the cook Nastasya in front of him, who brought him a plate of soup. He asks why the owner was beaten. The cook says that no one beat her, that it is the blood in him that is screaming. Raskolnikov falls into unconsciousness.

When Raskolnikov woke up on the fourth day, Nastasya and a young guy in a caftan with a beard, who “looked like an artel worker,” were standing at his bedside. The hostess looked out of the door, who “was shy and had a hard time enduring conversations and explanations, she was about forty years old, and she was fat and fat, black-browed and dark-eyed, kind from fatness and laziness; and she’s even very pretty.” Razumikhin enters. The guy in the caftan actually turns out to be an artel worker from the merchant Shelopaev. The artel worker reports that a transfer from his mother came through their office to Raskolnikov, and gives him 35 rubles.

Razumikhin tells Raskolnikov that Zosimov examined him and said that there was nothing serious, that he now dines here every day, since the hostess, Pashenka, honors him with all her heart, that he found him and got acquainted with the affairs, that he vouched for him and gave Chebarov ten rubles. He gives Raskolnikov the loan letter. Raskolnikov asks him what he was talking about in his delirium. He replies that he muttered something about earrings, chains, about Krestovy Island, about the janitor, about Nikodim Fomich and Ilya Petrovich, for some reason he was very interested in the sock, the fringe from the trousers. Razumikhin takes ten rubles and leaves, promising to return in an hour. After looking around the room and making sure that everything he was hiding remained in place, Raskolnikov falls asleep again. Razumikhin brings clothes from Fedyaev’s shop and shows them to Raskolnikov, and Nastasya makes her comments regarding the purchases.

To examine the sick Raskolnikov, a medical student named Zosimov comes, “a tall and fat man, with a puffy and colorless pale, smooth-shaven face, with straight blond hair, glasses and a large gold ring on a finger swollen with fat. He was twenty-seven years old... Everyone who knew him found him a difficult person, but they said that he knew his business.” There is a conversation about the murder of the old woman. Raskolnikov turns to the wall and examines the flower on the wallpaper, as he feels that his arms and legs are going numb. Meanwhile, Razumikhin reports that the dyer Mikolai has already been arrested on suspicion of murder, and Kokh and Pestryakov, who were detained earlier, have been released.

Mikolay drank for several days in a row, and then brought the tavern owner Dushkin a case with gold earrings, which he, in his words, “picked up on the panel.” After drinking a couple of glasses and taking change from one ruble, Mikolai ran away. He was detained after a thorough search “at a nearby outpost, at an inn,” where he wanted to hang himself drunk in a barn. Mikolai swears that he didn’t kill, that he found the earrings behind the door on the floor where he and Mitriy were painting. Zosimov and Razumikhin are trying to reconstruct the picture of the murder. Zosimov doubts that the real killer has been detained.

Pyotr Petrovich Luzhin arrives, “already middle-aged, prim, dignified, with a cautious and grumpy face,” and, looking around Raskolnikov’s “cramped and low “sea cabin,” he reports that his sister and mother are coming. “In general, Pyotr Petrovich was struck by something special, namely something that seemed to justify the title of “groom”, so unceremoniously given to him now. Firstly, it was clear, and even too noticeable, that Pyotr Petrovich was in a hurry to take advantage of the few days in the capital in order to have time to dress up and put on his make-up in anticipation of the bride, which, however, was very innocent and permissible.

Even one’s own, perhaps even too complacent, one’s own consciousness of his pleasant change for the better could be forgiven for such a case, for Pyotr Petrovich was on the groom’s line.” Luzhin regrets that he found Raskolnikov in such a state, reports that his sister and mother will temporarily stay in the rooms maintained by the merchant Yushin, that he has found an apartment for them, but temporarily he himself lives in the rooms of Mrs. Lippewechsel in the apartment of a friend, Andrei Semenych Lebezyatnikov. Luzhin talks about progress, which is driven by personal interest.

“If, for example, they still told me: “love” and I loved, then what came of it? - Pyotr Petrovich continued, perhaps with excessive haste, - what happened was that I tore my caftan in half, shared it with my neighbor, and both of us were left half naked, according to the Russian proverb: “You will follow several hares at once, and you will not achieve a single one.” Science says: love yourself first, first of all, for everything in the world is based on personal interest. If you love yourself alone, then you will manage your affairs properly and your caftan will remain intact. Economic truth adds that the more private affairs and, so to speak, entire caftans are organized in a society, the more solid foundations there are for it and the more common affairs are organized in it.

Therefore, by acquiring solely and exclusively for myself, I thereby acquire, as it were, for everyone and lead to the fact that my neighbor receives a somewhat more torn caftan, and no longer from private, individual generosity, but as a result of general prosperity.” There's talk of murder again. Zosimov reports that they are interrogating those who brought things to the old woman. Luzhin discusses the reasons for the increase in crime. Raskolnikov and Luzhin quarrel. Zosimov and Razumikhin, leaving Raskolnikov’s room, notice that Raskolnikov does not react to anything, “except for one point that makes him lose his temper: murder...”. Zosimov asks Razumikhin to tell him more about Raskolnikov. Nastasya asks Raskolnikov if he will drink tea. He frantically turns to the wall.

Left alone, Raskolnikov dresses in a dress bought by Razumikhin and leaves to wander the streets unnoticed by anyone. He is sure that he will not return home, because he needs to end his old life, he “doesn’t want to live like that.” He wants to talk to someone, but no one cares about him. He listens to the singing of women near the house, which was “all under drinking bars and other food establishments.” Gives it to the girl for a drink. He talks about someone who was sentenced to death: let it be on a high cliff above the ocean, let it be on a small platform where only two legs fit, but just to live. He reads newspapers in the tavern.

With Zametov, who was at the station during Raskolnikov’s fainting spell and later visited him during his illness, they begin to talk about murder. “Raskolnikov’s motionless and serious face transformed in an instant, and suddenly he burst into the same nervous laughter as before, as if he was completely unable to restrain himself. And in an instant he remembered with extreme clarity of sensation one recent moment when he was standing outside the door with an ax, the lock was jumping, they were swearing and breaking in behind the door, and he suddenly wanted to shout at them, swear at them, stick out his tongue at them, tease them , laugh, laugh, laugh, laugh!” Zametov notes that he is “either crazy or...”.

Raskolnikov talks about counterfeiters, and then, when the conversation returns to the murder, he says what he would do in the place of the murderer: he would hide the stolen things in a remote place under a stone and not take them out for a couple of years. Zametov again calls him crazy. “His eyes sparkled; he turned terribly pale; his upper lip trembled and jumped. He leaned over to Zametov as close as possible and began to move his lips without saying anything; This went on for about half a minute; he knew what he was doing, but he couldn't control himself. A terrible word, like the lock on the door at that time, was jumping on his lips: it was about to break; Just about to let him down, just about to pronounce him!” He asks Zametov: “What if I killed the old woman and Lizaveta?”, and then leaves. On the porch he runs into Razumikhin, who invites him to a housewarming party. Raskolnikov wants to be left alone, since he cannot recover due to the fact that he is constantly irritated.

On the bridge, Raskolnikov sees a woman throwing herself down and watching as they pull her out. Thinks about suicide.

He finds himself at “that” house, which he has not been to since “that” evening. “An irresistible and inexplicable desire drove him.” He curiously examines the stairs and notices that the apartment, which was being renovated, is locked. In the apartment where the murder took place, the walls are covered with new wallpaper. “For some reason Raskolnikov didn’t like this terribly; he looked at this new wallpaper with hostility, as if it was a pity that everything had changed so much.” When the workers asked Raskolnikov what he needed, he “got up, went out into the hallway, took the bell and pulled it.

The same bell, the same tinny sound! He pulled a second, third time; he listened and remembered. The former, painfully terrible, ugly sensation began to be recalled to him more and more vividly, he shuddered with every blow, and it became more and more pleasant for him.” Raskolnikov says that “there was a whole puddle here,” and now the blood has been washed away. Having gone down the stairs, Raskolnikov heads to the exit, where he meets several people, including a janitor who asks him why he came. “Watch,” Raskolnikov answers. The janitor and others decide that it is not worth messing with him and drive him away.

Raskolnikov sees a crowd of people surrounding a man who had just been crushed by horses, “thinly dressed, but in a “noble” dress, covered in blood.” The master's carriage is standing in the middle of the street, and the coachman is wailing that he shouted, saying he should be careful, but he was drunk. Raskolnikov recognizes Marmeladov in the unfortunate man. He asks to call the doctor and says that he knows where Marmeladov lives. The crushed man is carried home, where three children, Polenka, Lidochka and a boy, listen to Katerina Ivanovna’s memories of their past life. Marmeladov's wife undresses her husband, and Raskolnikov sends for the doctor. Katerina Ivanovna sends Polya to Sonya and shouts at those gathered in the room. Marmeladov is dying. They send for a priest.

The doctor, having examined Marmeladov, says that he is about to die. The priest confesses the dying man and then gives him communion, everyone prays. Sonya appears, “also in rags; her outfit was a penny, but decorated in a street style, according to the tastes and rules that had developed in her own special world, with a brightly and shamefully prominent purpose.” She “was short, about eighteen years old, thin, but quite pretty blonde, with wonderful blue eyes.” Before his death, Marmeladov asks his daughter for forgiveness. Dies in her arms. Raskolnikov gives Katerina Ivanovna twenty-five rubles and leaves. In the crowd he bumps into Nikodim Fomich, whom he has not seen since the scene in the office.

Nikodim Fomich says to Raskolnikov: “How did you, however, wet yourself with blood,” to which he remarks: “I’m covered in blood.” Raskolnikov is caught up by Polenka, who was sent for him by his mother and Sonya. Raskolnikov asks her to pray for him and promises to come tomorrow. He thought: “Strength, strength is needed: without strength you can’t take anything; but strength must be obtained by force, that’s what they don’t know.” “Pride and self-confidence grew in him every minute; the very next minute he became a different person from the previous one.” He goes to Pazumikhin.

He accompanies him home and during the conversation admits that Zametov and Ilya Petrovich suspected Raskolnikov of murder, but Zametov now repents of this. He adds that the investigator, Porfiry Petrovich, wants to meet him. Raskolnikov says that he saw one man die, and that he gave all the money to his widow.

As they approach the house, they notice a light in the window. Raskolnikov's mother and sister are waiting in the room. Seeing him, they joyfully rush towards him. Rodion loses consciousness. Razumikhin calms the women. They are very grateful to him, as they have heard about him from Nastasya.

PART THREE

Having come to his senses, Raskolnikov asks Pulcheria Alexandrovna, who intended to stay overnight near her son, to return to where she and Dunya were staying. Razumikhin promises that he will stay with him. Raskolnikov tells his sister and mother, whom he has not seen for three years, that he kicked Luzhin out. He asks his sister not to marry this man, because he does not want such a sacrifice from her. Mother and sister are at a loss. Razumikhin promises them that he will sort everything out. “He stood with both ladies, grabbing them both by the hands, persuading them and presenting reasons to them with amazing frankness and, probably for greater conviction, with almost every word he said, tightly, tightly, as if in a vice, he squeezed both their hands until it hurt and seemed to be devouring Avdotya Romanovna with his eyes, not at all embarrassed by it...

Avdotya Romanovna, although she was not of a timid nature, met with amazement and almost even fear the glances of her brother’s friend sparkling with wild fire, and only the boundless confidence inspired by Nastasya’s stories about this strange man kept her from trying to run away from him and drag her along with her. your mother." Razumikhin accompanies both ladies to the rooms where they are staying. Dunya tells her mother that “you can rely on him.” She “was remarkably good-looking - tall, amazingly slender, strong, self-confident - which was expressed in every gesture of hers and which, however, did not in the least take away from her movements the softness and gracefulness. Her face was similar to her brother, but she could even be called a beauty. Her hair was dark brown, a little lighter than her brother's; the eyes are almost black, sparkling, proud and at the same time, sometimes, for minutes, unusually kind.

She was pale, but not sickly pale; her face shone with freshness and health. Her mouth was a little small, but her lower lip, fresh and scarlet, protruded slightly forward.” Her mother looked younger than her forty-three years. “Her hair was already beginning to turn gray and thin, small radiant wrinkles had long appeared around her eyes, her cheeks were sunken and dry from care and grief, and yet this face was beautiful. It was a portrait of Dunechkin’s face, only twenty years later.” Razumikhin brings Zosimov to the women, who tells them about Raskolnikov’s condition. Razumikhin and Zosimov leave. Zosimov remarks: “What a delightful girl this Avdotya Romanovna is!” This causes an angry outburst from Razumikhin.

In the morning, Razumikhin understands that “something extraordinary happened to him, that he accepted into himself one impression that was completely unknown to him and unlike all the previous ones.” He is afraid to think about yesterday’s meeting with Raskolnikov’s relatives, since he was drunk and did a lot of inappropriate things. He sees Zosimov, who reproaches him for talking a lot. After this, Razumikhin goes to Bakaleev’s rooms, where the ladies are staying. Pulcheria Alexandrovna asks him about her son. “I’ve known Rodion for a year and a half: he’s gloomy, gloomy, arrogant and proud,” says Razumikhin, “lately (and maybe much earlier) he’s been suspicious and a hypochondriac.

Generous and kind. He doesn’t like to express his feelings and would rather commit cruelty than express his heart in words. Sometimes, however, he is not a hypochondriac at all, but simply cold and insensitive to the point of inhumanity, really, as if two opposing characters alternately alternate in him. Sometimes he's terribly taciturn! He has no time for everything, everyone interferes with him, but he lies there and does nothing. Not mockingly, and not because there was a lack of wit, but as if he didn’t have enough time for such trifles. Doesn't listen to what they say. Never interested in what everyone else is interested in at the moment. He values himself terribly highly and, it seems, not without some right to do so.”

They talk about how Raskolnikov wanted to get married, but the wedding did not take place due to the death of the bride. Pulcheria Alexandrovna says that in the morning they received a note from Luzhin, who was supposed to meet them at the station yesterday, but sent a footman, saying that he would come the next morning. Luzhin did not come as promised, but sent a note in which he insists that “at the general meeting” Rodion Romanovich “is no longer present,” and also brings to their attention that Raskolnikov gave all the money that his mother gave him, “ a girl of notorious behavior,” the daughter of a drunkard who was run over by a carriage. Razumikhin advises to do as Avdotya Romanovna decided, in whose opinion it is necessary for Rodion to come to them at eight o’clock. Together with Razumikhin, the ladies go to Raskolnikov. Climbing the stairs, they see that the hostess's door is slightly open and someone is watching from there. As soon as they reach the door, it suddenly slams shut.

The women enter the room where Zosimov meets them. Raskolnikov put himself in order and looked almost healthy, “only he was very pale, absent-minded and gloomy. From the outside, he looked like a wounded person or someone enduring some kind of severe physical pain: his eyebrows were knitted, his lips were compressed, his eyes were inflamed.” Zosimov notes that with the arrival of his relatives, he had “a heavy hidden determination to endure an hour or two of torture, which could no longer be avoided... He later saw how almost every word of the ensuing conversation seemed to touch some wound of his patient and reopen it; but at the same time, he was partly amazed at today’s ability to control himself and hide his feelings of yesterday’s monomaniac, who yesterday almost flew into a rage because of the slightest word.”

Zosimov tells Raskolnikov that recovery depends only on himself, that he needs to continue his studies at the university, since “work and a firmly set goal” could greatly help him. Raskolnikov tries to calm his mother down, tells her that he was going to come to them, but “the dress was delayed,” since it was in the blood of one official who died and whose wife received from him all the money that his mother sent him. And he adds: “However, I had no right, I confess, especially knowing how you yourself got this money.

To help, you must first have the right to do so.” Pulcheria Alexandrovna reports that Marfa Petrovna Svidrigailova has died. Raskolnikov notes that they will still have time to “talk.” “One recent terrible sensation passed through his soul like a dead cold; again it suddenly became completely clear and understandable to him that he had just told a terrible lie, that not only would he never have time to talk, but now he couldn’t talk about anything else, never with anyone.” Zosimov leaves. Raskolnikov asks his sister if she likes Razumikhin.

She answers: “Very.” Rodion recalls his love for his master’s daughter, who was always sick, loved to give to the poor and dreamed of a monastery. The mother compares her son's apartment to a coffin and notices that because of her he has become so melancholic. Dunya, trying to justify herself to her brother, says that she is getting married primarily for her own sake.

Raskolnikov reads Luzhin's letter, which his sister and mother show him, and notices that Luzhin "writes illiterately." Avdotya Romanovna stands up for him: “Peter Petrovich does not hide the fact that he studied with copper money, and even boasted that he paved the way for himself.” Dunya asks her brother to come to them in the evening. She also invites Razumikhin.

Sonya Marmeladova enters the room. “Now it was a modestly and even poorly dressed girl, still very young, almost like a girl, with a modest and decent manner, with a clear, but seemingly somewhat frightened face. She was wearing a very simple house dress, and on her head was an old hat of the same style; only in my hands was, as yesterday, an umbrella.” Raskolnikov “suddenly saw that this humiliated creature was already so humiliated that he suddenly felt sorry.”

The girl says that Katerina Ivanovna sent her to invite Raskolnikov to the wake. He promises to come. Pulcheria Alexandrovna and her daughter do not take their eyes off their guest, but when they leave, only Avdotya Romanovna says goodbye to her. On the street, the mother tells her daughter that she is like her brother not in face, but in soul: “...you are both melancholic, both gloomy and hot-tempered, both arrogant and both generous.” Dunechka reassures her mother, who is worried about how this evening will go. Pulcheria Alexandrovna admits that she is afraid of Sonya.

Raskolnikov, in a conversation with Razumikhin, notices that the old woman had in pawn his silver watch, which passed to him from his father, as well as the ring that his sister gave him. He wants to take these things. Razumikhin advises contacting the investigator, Porfiry Petrovich, about this.

Raskolnikov accompanies Sonya to the corner, takes her address and promises to come by. Left alone, she feels something new in herself. “A whole new world unknown and dimly descended into her soul.” Sonya is afraid that Raskolnikov will see her wretched room.

A man is watching Sonya. “He was a man of about fifty, above average height, portly, with broad and steep shoulders, which gave him a somewhat stooped appearance. He was smartly and comfortably dressed and looked like a dignified gentleman. In his hands was a beautiful cane, which he tapped along the sidewalk with every step, and his hands were in fresh gloves. His wide, high-cheekbone face was quite pleasant, and his complexion was fresh, not St. Petersburg.

His hair, still very thick, was completely blond and just a little gray, and his wide, thick beard, hanging down like a shovel, was even lighter than his head hair. His eyes were blue and looked coldly, intently and thoughtfully; lips are scarlet." He follows her and, having found out where she lives, is glad that they are neighbors.

On the way to Porfiry Petrovich, Razumikhin is noticeably worried. Raskolnikov teases him and laughs loudly. Just like that, with a laugh, he enters Porfiry Petrovich.

Raskolnikov offers his hand to Porfiry Petrovich, Razumikhin, waving his hand, accidentally knocks over the table with a glass of tea standing on it and, embarrassed, goes to the window. Zametov is sitting on a chair in the corner, looking at Raskolnikov “with some kind of confusion.” “Porfiry Petrovich was dressed at home, in a dressing gown, very clean underwear and worn out shoes. He was a man of about thirty-five, shorter than average height, plump and even paunchy, shaven, without a mustache or sideburns, with tightly cropped hair on a large round head, somehow especially convexly rounded at the back of the head.

His plump, round and slightly snub-nosed face was the color of a sick, dark yellow, but rather cheerful and even mocking. It would even be kind and soulful if the expression of the eyes, with some kind of liquid watery shine, covered with almost white eyelashes, blinking as if winking at someone, did not interfere. The look of these eyes somehow strangely did not harmonize with the whole figure, which even had something feminine about it, and gave it something much more serious than could be expected from it at first glance.” Raskolnikov is sure that Porfiry Petrovich knows everything about him.

He talks about his things pledged and hears that they were found wrapped in one piece of paper, on which his name and the day of the month were written in pencil when the pawnbroker received them. Porfiry Petrovich notices that all the pawnbrokers are already known and that he was waiting for Raskolnikov’s arrival.

A dispute arises about the essence and causes of crimes. The investigator recalls Raskolnikov’s article entitled “On the Crime,” which was published in Periodical Rech two months ago. Raskolnikov is perplexed how the investigator knew about the author, since she was “signed with a letter.” The answer follows immediately: from the editor. Porfiry Petrovich reminds Raskolnikov that, according to his article, “the act of executing a crime is always accompanied by illness,” and all people “are divided into “ordinary” and “extraordinary.”

Raskolnikov explains that, in his opinion, “everyone who is not only great, but also a little out of the rut, that is, even a little bit capable of saying something new,” must be criminals. Any sacrifices and crimes can be justified by the greatness of the purpose for which they were committed. An ordinary person is not able to behave like someone who “has the right.” Very few extraordinary people are born; their birth must be determined by the law of nature, but it is still unknown. An ordinary person will not go to the end, he will begin to repent.

Razumikhin is horrified by what he heard, that Raskolnikov’s theory allows “blood to be shed according to conscience.” The investigator asks Raskolnikov whether he himself would decide to kill “to somehow benefit all of humanity.” Raskolnikov replies that he does not consider himself either Mohammed or Napoleon. “Who in Rus' doesn’t consider himself Napoleon now?” — the investigator grins. Raskolnikov asks whether he will be officially interrogated, to which Porfiry Petrovich replies that “for now this is not required at all.”

The investigator asks Raskolnikov what time he was in the house where the murder took place, and whether he saw two dyers on the second floor. Raskolnikov, not suspecting what the trap is, says that he was there at eight o’clock, but did not see the dyers. Razumikhin shouts that Raskolnikov was in the house three days before the murder, and the dyers were painting on the day of the murder. Porfiry Petrovich apologizes for confusing the dates. Razumikhin and Raskolnikov go out into the street “gloomy and gloomy.” “Raskolnikov took a deep breath...”

On the way, Raskolnikov and Razumikhin discuss the meeting with Porfiry Petrovich. Raskolnikov says that the investigator does not have facts to accuse him of murder. Razumikhin is indignant that all this looks “offensive.” Raskolnikov understands that Porfiry is “not so stupid at all.” “I get the taste at other points!” - he thinks. When they approach Bakaleev’s rooms, Raskolnikov tells Razumikhin to go up to his sister and mother, and he hurries home, since it suddenly seemed to him that there might be something left in the hole where he hid the old woman’s things immediately after the murder. Not finding anything, he goes out and sees a tradesman talking about him with the janitor. Rodion asks what he needs.

The tradesman leaves, and Raskolnikov runs after him, asking him the same question. He throws in his face: “Murderer!”, and then leaves, Raskolnikov follows him with his gaze. Returning to his closet, he lies for half an hour. When he hears that Razumikhin is coming up to him, he pretends to be asleep, and he, barely looking into the room, leaves. He begins to think, feeling his physical weakness: “The old woman was only sick... I wanted to get over it as quickly as possible... I didn’t kill a person, I killed a principle! I killed the principle, but I didn’t step over it, I stayed on this side...

All he managed to do was kill. And even then he failed, it turns out...” He calls himself a louse, because he talks about this, since “for a whole month he disturbed the all-good providence, calling as witnesses that he was not undertaking it for his own, they say, flesh and lust, but has in it a magnificent and pleasant goal in sight”: “...I myself, perhaps, am even nastier and nastier than a killed louse, and I had a presentiment in advance that I would tell myself this after I kill!” He comes to the conclusion that he is a “trembling creature”, as he thinks about the correctness of what he has done.

Raskolnikov has a dream. He is on the street where there are a lot of people. On the sidewalk a man waves to him. He recognizes him as a former tradesman who turns and slowly walks away. Raskolnikov follows him. He climbs the stairs, which seem familiar to him. He recognizes the apartment where he saw the workers. The tradesman was obviously hiding somewhere. Raskolnikov enters the apartment. An old woman sits on a chair in the corner, whom he hits on the head with an ax several times. The old woman laughs. He is overcome by rage, he hits and hits the old woman on the head with all his might, but she only laughs even more. The apartment is full of people watching what is happening and saying nothing, waiting for something. He wants to scream, but wakes up. There is a man in his room. Raskolnikov asks what he needs. He introduces himself - this is Arkady Ivanovich Svidrigailov.

PART FOUR

While Raskolnikov is wondering if he is dreaming, his guest explains that he came to meet him and asks him to help him “in one enterprise” that directly concerns Dunya’s interest. Svidrigailov is trying to prove that it is not true that he stalked an innocent girl in his house, since he is capable of deep feelings. Raskolnikov wants the uninvited guest to leave, but he intends to speak out. Raskolnikov listens to Svidrigailov, who considers himself innocent of his wife’s death. In his youth, Svidrigailov was a sharper, caroused, and made debts, for which he was sent to prison. Marfa Petrovna bought him for “thirty thousand pieces of silver.” For seven years they lived in the village, without leaving anywhere.

On his name day, his wife gave him a document about these 30 thousand, written out in someone else’s name, as well as a significant amount of money. He admits that he has already seen a ghost three times since his wife’s death, to which Raskolnikov suggests that he go to the doctor. Svidrigailov suggests that “ghosts are, so to speak, scraps and fragments of other worlds, their beginning. A healthy person, of course, has no need to see them, because a healthy person is the most earthly person, and therefore, must live only this life here, for completeness and for order.

Well, the moment you get sick, the normal earthly order in the body is slightly disrupted, the possibility of another world immediately begins to take its toll, and the more sick you are, the more contacts with another world there are, so that when a completely human person dies, he will directly pass on to another world " He says that Avdotya Romanovna should not marry, that he is going to propose to her himself. He offers his assistance in disrupting Dunya’s wedding with Luzhin, and is ready to offer Avdotya Romanovna ten thousand rubles, which he does not need. It was precisely because his wife “concocted” this alliance that he had a fight with her. Marfa Petrovna also indicated in her will that Dunya should be given three thousand rubles. He asks Raskolnikov to arrange a meeting with his sister. After that, he leaves and runs into Razumikhin at the door.

On the way to Bakaleev, Razumikhin asks who was with Raskolnikov. Raskolnikov explains that this is Svidrigailov, a “very strange” man who “decided on something,” and notes that Dunya must be protected from him. Razumikhin admits that he visited Porfiry and wanted to call him to talk, but nothing happened. In the corridor they run into Luzhin, so the three of them enter the room. Mother and Luzhin talk about Svidrigailov, whom Pyotr Petrovich calls “the most depraved and lost in vices of all people of this kind.”

Luzhin says that Marfa Petrovna mentioned that her husband knew a certain Resslich, a small pawnbroker. She lived with a deaf-mute fourteen-year-old relative who hanged herself in the attic. According to the denunciation of another German woman, the girl committed suicide because Svidrigailov abused her, and only thanks to the efforts and money of Marfa Petrovna, her husband managed to avoid punishment. From Luzhin’s words it becomes known that Svidrigailov also drove Philip’s servant to suicide. Dunya objects, testifying that he treated the servants well. Raskolnikov reports that about an hour and a half ago, Svidrigailov came to him, who wants to meet Dunya in order to make her a lucrative offer, and that according to Marfa Petrovna’s will, Dunya is entitled to three thousand rubles.

Luzhin notes that his demand has not been fulfilled, and therefore he will not talk about serious matters in front of Raskolnikov. Dunya tells him that she intends to make a choice between Luzhin and her brother, she is afraid of making a mistake. According to Luzhin, “love for your future life partner, for your husband, should exceed love for your brother.” Raskolnikov and Luzhin sort things out. Luzhin tells Duna that if he leaves now, he will never return, reminds him of his costs. Raskolnikov kicks him out. Going down the stairs, Pyotr Petrovich still imagines that the matter “may not be completely lost yet and, as far as some ladies are concerned, even “very, very” fixable.”

“Pyotr Petrovich, having risen from insignificance, became painfully accustomed to admiring himself, highly valued his intelligence and abilities, and even sometimes, alone, admired his face in the mirror. But more than anything else in the world, he loved and valued his money, obtained through labor and all sorts of means: it made him equal to everything that was higher than him.” He wanted to marry a poor girl in order to dominate her. A beautiful and smart wife would help him make a career.

After Luzhin leaves, Pulcheria Alexandrovna and Dunechka rejoice at the break with Pyotr Petrovich. Razumikhin is absolutely delighted. Raskolnikov conveys to those present his conversation with Svidrigailov. Dunya is interested in her brother’s opinion. It seems to her that she needs to meet with Svidrigailov. Plans for his and Dunya’s future are already spinning in Razumikhin’s head. He says that with the money the girl gets and his thousand, he can start publishing books. Dunya supports Razumikhin's ideas. Raskolnikov also speaks approvingly of them.

Unable to get rid of thoughts of murder, Raskolnikov leaves, noting in parting that perhaps this meeting will be their last. Dunya calls him “an insensitive, evil egoist.” Raskolnikov waits for Razumikhin in the corridor, and then asks him not to leave his mother and sister. “They looked at each other in silence for a minute. Razumikhin remembered this moment all his life. Raskolnikov’s burning and intent gaze seemed to intensify with every moment, penetrating into his soul, into his consciousness. Suddenly Razumikhin shuddered. Something strange seemed to pass between them... Some idea slipped through, like a hint; something terrible, ugly and suddenly understood on both sides... Razumikhin turned pale as death.” Returning to Raskolnikov’s relatives, Razumikhin calmed them down as best he could.

Raskolnikov comes to Sonya, who lived in a wretched room, which “looked like a barn, had the appearance of an irregular quadrangle.” There was almost no furniture: a bed, a table, two wicker chairs, a simple wooden chest of drawers. “The poverty was visible.” Raskolnikov apologizes for showing up so late. He came to say “one word”, since perhaps they would not see each other again. Sonya says that it seemed to her that she saw her father on the street, admits that she loves Katerina Ivanovna, who, in her opinion, is “pure”: “She so believes that there must be justice in everything, and demands... And although torture her, but she will not do injustice.”

The owner intends to throw her and the children out of the apartment. Sonya says that Katerina Ivanovna is crying, completely crazy with grief, she keeps saying that she will go to her city, where she will open a boarding house for noble maidens, and fantasizes about the future “wonderful life.” They wanted to buy shoes for the girls, but they didn’t have enough money. Katerina Ivanovna is sick with consumption and will soon die. Raskolnikov “with a cruel grin” says that if Sonya suddenly gets sick, the girls will have to follow her own path.

She objects: “God will not allow such horror!” Raskolnikov rushes around the room, and then approaches Sonya and, bending down, kisses her foot. The girl recoils from him. “I didn’t bow to you, I bowed to all human suffering,” says Raskolnikov and calls her a sinner who “killed and betrayed herself in vain.” He asks Sonya why she doesn't commit suicide. She says that her family will be lost without her. He thinks that she has three roads: “to throw herself into a ditch, end up in a madhouse or... or, finally, throw herself into debauchery, which stupefies the mind and petrifies the heart.”

Sonya prays to God, and on her chest of drawers she has the Gospel, which was given to her by Lizaveta, the sister of the murdered old woman. It turns out that they were friendly. Raskolnikov asks to read from the Gospel about the resurrection of Lazarus. Sonya, having found the right place in the book, reads, but falls silent. Raskolnikov understands that it is difficult for her to “expose everything that is hers. He realized that these feelings really seemed to constitute her real and already long-standing, perhaps, secret.” Sonya, having overcome herself, begins to read intermittently. “She was approaching the word about the greatest and unheard of miracle, and a feeling of great triumph overwhelmed her.” She thought that Raskolnikov would now hear him and believe.

Raskolnikov admits that he abandoned his family and suggests to Sonya: “Let’s go together... I came to you. We are cursed together, we will go together!” He explains to her that he needs her, that she “also overstepped... was able to overstep”: “You laid hands on yourself, you ruined your life... yours (it’s all the same!) You could live in spirit and mind, but cum on Sennaya... But you can’t stand it and if you’re left alone, you’ll go crazy, like me. You’re already like crazy; Therefore, we must go together, along the same road! Let's go to!" Sonya doesn't know what to think. Raskolnikov says: “Afterwards you will understand... Freedom and power, and most importantly power! Over all the trembling creatures and over the entire anthill! He adds that he will come to her tomorrow and tell her the name of the killer, since he chose her. Leaves. Sonya has been delirious all night. Svidrigailov overheard their entire conversation, hiding in the next room behind the door.

In the morning, Rodion Raskolnikov enters the investigative police department and asks to be received by Porfiry Petrovich. “The most terrible thing for him was to meet this man again: he hated him beyond measure, endlessly, and was even afraid of somehow revealing himself with his hatred.” During a conversation with Porfiry Petrovich, Raskolnikov feels anger gradually growing in him. He says that he came for interrogations, that he is in a hurry to attend the funeral of an official crushed by horses. He is clearly nervous, but Porfiry Petrovich, on the contrary, is calm, winks at him from time to time, smiles.

Porfiry Petrovich explains to Raskolnikov why it takes them so long to start a conversation: if two people who mutually respect each other get together, then within half an hour they cannot find a topic for conversation, because “they become numb in front of each other, sit and are mutually embarrassed.” He penetrates Raskolnikov’s psychology, he understands that he is a suspect. Porfiry Petrovich indirectly accuses Raskolnikov. He says that the killer is temporarily free, but he will not run away from him: “Did you see the butterfly in front of the candle? Well, so he will all be, everything will be around me, like around a candle, spinning; freedom will not be nice, it will begin to think, get confused, entangle itself all around, as if in a net, worry itself to death!”

After Porfiry Petrovich’s next monologue, Raskolnikov tells him that he is convinced that he is suspected of committing a crime, and declares: “If you have the right to legally persecute me, then persecute me; arrest, then arrest. But I won’t allow myself to laugh in my own eyes and torment myself.” Porfiry Petrovich tells him that he knows about how he went to rent an apartment late at night, how he rang the bell, and was interested in blood. He notices that Razumikhin, who just recently tried to find out this or that from him, is “too kind a person for that,” tells a “painful case” from practice, and then asks Raskolnikov if he would like to see the “surprise, sir,” which he has it under lock and key. Raskolnikov is ready to meet with anyone.

There is a noise behind the door. A pale man appears in the office, whose appearance was strange. “He looked straight ahead, but as if not seeing anyone. Determination sparkled in his eyes, but at the same time a mortal pallor covered his face, as if he had been led to execution. His completely white lips trembled slightly. He was still very young, dressed like a commoner, average height, thin, with hair cut in a circle, with thin, seemingly dry features.” This is the arrested dyer Nikolai, who immediately admits that it was he who killed the old woman and her sister. Porfiry Petrovich finds out the circumstances of the crime.

Remembering Raskolnikov, he says goodbye to him, hinting that this will not be the last time they see each other. Raskolnikov, already at the door, asks ironically: “Aren’t you going to show me a surprise?” He understands that Nikolai lied, the lie will come to light and then they will attack him. Returning home, he thinks: “I’m late for the funeral, but I have time for the wake.” Then the door opened, and “a figure appeared - yesterday’s man from underground.” He was among the people standing at the gate of the house where the murder took place on the day when Raskolnikov came there. The janitors did not go to the investigator, so he had to do it. He asks for forgiveness from Raskolnikov “for the slander and for the malice”, says that he left Porfiry Petrovich’s office after him.

PART FIVE

After the explanations with Dunechka and her mother, Luzhin’s pride was pretty wounded. He, looking at himself in the mirror, thinks that he will find himself a new bride. Luzhin was invited to the wake along with his neighbor Lebezyatnikov, whom he “despised and hated even beyond measure, almost from the very day he moved in with him, but at the same time seemed to be somewhat afraid.” Lebezyatnikov is a supporter of “progressive” ideas. Finding himself in St. Petersburg, Pyotr Petrovich decides to take a closer look at this man, to find out more about his views in order to have some idea about the “younger generations.”

Lebezyatnikov defines his calling in life as “protest” against everyone and everything. Luzhin asks him if he will go to Katerina Petrovna’s wake. He replies that he won’t go. Luzhin notes that after Lebezyatnikov beat up Marmeladov’s widow a month ago, he should be ashamed. The conversation turns to Sonya. According to Lebezyatnikov, Sonya’s actions are a protest against the structure of society, and therefore she is worthy of respect.

He tells Luzhin: “You just despise her. Seeing a fact that you mistakenly consider worthy of contempt, you are already denying a human being a humane view of him.” Luzhin asks to bring Sonya. Lebezyatnikov brings. Luzhin, who was counting the money that was lying on the table, seats the girl opposite. She cannot take her eyes off the money and is ashamed of looking at it. Luzhin invites her to organize a lottery in her favor and gives her a ten-ruble credit card. Lebezyatnikov did not expect that Pyotr Petrovich was capable of such an act. But Luzhin was up to something vile, and therefore he rubbed his hands in excitement. Lebezyatnikov recalled this later.

Katerina Ivanovna spent ten rubles on the funeral. Perhaps she was driven by the “pride of the poor,” when they spend their last savings “just to be “no worse than others” and so that others “don’t judge” them in some way.” Amalia Ivanovna, the landlady, helped her with everything regarding preparations. Marmeladov's widow is nervous due to the fact that there were few people at the funeral, and only the poor at the wake. Mentions Luzhin and Lebezyatnikov in the conversation.

Raskolnikov arrives at the moment when everyone is returning from the cemetery. Katerina Ivanovna is very happy about his appearance. She finds fault with Amalia Ivanovna, treats her “extremely carelessly.”

Even if you managed to get acquainted with Dostoevsky’s work in the summer, you, of course, cannot remember everything: some little things are forgotten, the names of minor characters are erased from memory, but in literature lessons you always need to be prepared for the most tricky questions. During school hours there is not enough time to leaf through Crime and Punishment, so we offer you a brief chapter-by-chapter retelling. And if you still think that the whole point of this story is the murder of the old woman, then we suggest you take a couple of minutes to read.

The main character Rodion Raskolnikov is a former student living in a closet located in St. Petersburg (here is his detailed description). Only in the novel this is not a majestic city at all: stuffiness, stench, crowding, drunken people and oppressive poverty are described (here). In the first chapter, readers are immediately given a portrait of the old pawnbroker Alena Ivanovna, consisting of repulsive features: a decrepit and greedy woman mired in greed. Raskolnikov goes to the old woman to look around and check his feelings, pawning her expensive things.

The Marmeladov family is also not long in coming, and the former official, alcoholic Semyon Marmeladov, meets Raskolnikov in a tavern (here). There he tells Rodion about his family living in poverty and about his daughter Sonya, who lives “on a yellow ticket” to feed her father’s family. The main character also receives a letter from his mother, which tells about Raskolnikov’s sister Duna, the landowner Svidrigailov and the businessman Luzhin. Dunya was insulted by his harassment by the owner of the house where she served as a governess. Now she can no longer work. And she takes a desperate step - an engagement to a wealthy but unloved man - Luzhin (here are them).

Immediately in the first part, Raskolnikov decides that there will be a crime. He has a noble goal, but he is tormented by doubts about the correctness of this action. However, he sees signs that push him to kill: an overheard conversation between a student and an officer in a tavern about the justice of the possible murder of an old woman, about the fact that Lizaveta (Alena Ivanovna’s sister) will not be home tomorrow evening (described in detail here). The first part ends with a crime committed by Raskolnikov: the author describes the deliberate murder and robbery of an old pawnbroker and the accidental murder of her pregnant sister Lizaveta. Rodion is very afraid, he doesn’t even manage to make the decisive blow the first time. He is caught with his body stretched out by the victim's sister, whom he also does not leave alive. Then, as if in a fever, he leaves the house, taking the valuables that accidentally caught his eye, without even really searching the apartment. On the way, he barely hides from random passers-by at the entrance, so as not to be recognized.

Part II

All subsequent parts of the novel can be called the punishment of the main character; immediately after the crime, he experiences horror, confusion and fear. Raskolnikov is summoned to the police office, which undoubtedly frightens him: however, the reason for the call is the complaint of the apartment owner for non-payment. An inexperienced criminal begins to give himself away when he faints during an overheard conversation about the murder of an old pawnbroker.

Raskolnikov hides everything stolen under a stone in an unfamiliar courtyard, and even this makes it clear to the reader how useless the hero’s crime was. Rodion, weakened and ill from exertion, is helped by his university friend Razumikhin, providing him with food and clothing (here they are). In the same part, Raskolnikov’s unsuccessful acquaintance with Luzhin will take place. Both men immediately developed a mutual antipathy for each other. The brother is tormented; he is unable to accept such a sacrifice from his sister, because she is selling herself so that he can continue his studies.

The second part ends with a terrible tragedy: Marmeladov falls under a horse and dies, Sonya appears. Raskolnikov gives the money that his mother sent him for the funeral of the Marmeladov family (here is a description of them). The hero admitted to himself that at that moment he was living, and not just existing. In a dirty little room, he saw the unfortunate kids and their mother, Katerina Ivanovna, sick with consumption. All of them are supported by the pale and thin girl Sonya (here is her), the only natural daughter of the deceased, who sells herself for the survival of her stepmother and her offspring.

Part III

Raskolnikov's mother and sister come to see him. Razumikhin’s love for Dunya is visible to the naked eye. Raskolnikov is outraged by Luzhin’s letter, where the groom writes to his relatives that Rodion gave money to a “girl of notorious behavior.” Trying to prove that Luzhin distorted the situation, Raskolnikov sits Sonya, who came to invite the hero to the wake, next to his mother and sister.

In the third part, Raskolnikov will finally meet the talented investigator Porfiry Petrovich, who has no evidence against the main character, but has exceptional intuition. We hear a conversation about Raskolnikov’s theory, which is set out in the article “On Crime,” written by a young man six months before the murder of Alena Ivanovna (here). Raskolnikov sets out the essence of his theory about ordinary people who are inclined to obedience and humility, and extraordinary people who are allowed to break the law if this is required for an important idea. Having explained his assumption about “trembling creatures that have the right,” the nervous and feverish Rodion only arouses Porfiry Petrovich’s suspicion even more.

Part IV

In the fourth part of Dostoevsky’s novel, the reader meets Svidrigailov, the very owner of the house where Dunya was disgraced by the master’s dirty advances. This libertine comes to Raskolnikov and, noticing a kindred spirit in him, admits that the ghosts of his victims appear to him. He has long lived only by voluptuousness and has already ruined many women’s destinies.

Dunya and Luzhin quarrel and break off their engagement, and Raskolnikov drops in to see Sonya. The hero tells her that her sin is that she “killed and betrayed herself in vain.” Marmeladova reads to Rodion the biblical legend about the resurrection of Lazarus, trying to convey to him the meaning of her self-denial and hope for a favorable outcome.

Raskolnikov is again at the police station, with Porfiry Petrovich. Psychologically unable to withstand the pressure, he shouts:

Arrest me, search me, but please act according to form and not play with me!

However, the unexpected confession of the painter Nikolai in the murder of the pawnbroker puts Raskolnikov in a stupor. The investigator understands who is guilty, but cannot do anything without a frank confession from the criminal.

Part V

Luzhin talks with Sonya, and at Marmeladov’s wake he slips her money in order to later quarrel between Raskolnikov and his sister and mother. He tries to accuse the girl of stealing money, but Lebezyatnikov and Raskolnikov defend her. The slanderer is driven away in disgrace.

Raskolnikov confesses to Sonya about the murder. Rodion tries to prove to her that he tried to kill the “useless, disgusting, harmful” louse; Sonya advises “accepting suffering and redeeming yourself with it.” Later it turns out that their conversation was overheard by Svidrigailov, who lives next door.

Katerina Ivanovna dies in Sonya's room from a throat bleed, and Svidrigailov pays for her funeral and the lives of her children. He is afraid of fate's retribution for his sins; the awareness of his own depravity drives him crazy.

Part VI

In the final part of the novel, Porfiry Petrovich looks at Raskolnikov; at the end of their conversation, the investigator is convinced that it was Raskolnikov who killed the pawnbroker and invites him to “make a confession.” Dunya is with Svidrigailov: he informs her about her brother’s crime. He also tries to woo her, but the woman leaves him. After she leaves, Svidrigailov is tormented by nightmares and commits suicide.

Raskolnikov's mother is unwell, they say goodbye to their son.

She had long understood that something terrible was happening to her son, and now some terrible moment had arrived for him.

After talking first with Dunya, then with Sonya, Raskolnikov repented in the middle of the square, kissing the dirty ground “with pleasure and happiness,” after which Rodion confessed to the police.

Epilogue

It is in the epilogue that the end of the story is revealed to us, hope is given for the future of Raskolnikov and Sonya, and the long-awaited resurrection of the hero takes place (it is described in detail).

In the final chapter of the novel, Raskolnikov is in Siberia, in hard labor. Sonya Marmeladova is next to the main character, who in the epilogue realizes his love for her. Previously, her presence, her self-denial, infuriated him. It seemed to him that by her behavior she seemed to be reproaching him and obliging him to do something. This kind and sincere girl developed good relationships with the prisoners. But over time, he realized how beautiful and kind this girl was, how beneficial her influence was.

Readers are told about the trial of Rodion. Raskolnikov’s dreams play an important role in the work, and the hero’s final dream for us shows a pestilence, because of which everyone thought that the truth lay in him (detailed here). Thanks to this terrible dream, where everything perished, Raskolnikov finally realizes the inhumane meaning of his own theory and repents of the crime he committed.

Interesting? Save it on your wall!Fedor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. Crime and Punishment, Part One

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

Fedor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. Crime and Punishment A novel in six parts with an epilogue

* PART ONE *

On an exceptionally hot evening early in July a young man came out of the garret in which he lodged in S. Place and walked slowly, as though in hesitation, towards K. bridge.

At the beginning of July, in an extremely hot time, in the evening, one young man came out of his closet, which he had rented from tenants in the S-th lane, onto the street and slowly, as if in indecision, went to the K-n bridge.

He had successfully avoided meeting his landlady on the staircase.

He successfully avoided meeting his mistress on the stairs.

His garret was under the roof of a high, five-storied house and was more like a cupboard than a room.

His closet was right under the roof of a tall five-story building and looked more like a closet than an apartment.

The landlady who provided him with garret, dinners, and attendance, lived on the floor below, and every time he went out he was obliged to pass her kitchen, the door of which invariably stood open.

His landlady, from whom he rented this closet with dinner and servants, was located one staircase down, in a separate apartment, and every time, when going out into the street, he certainly had to pass by the landlady’s kitchen, which was almost always wide open to the stairs.

And each time he passed, the young man had a sick, frightened feeling, which made him scowl and feel ashamed.

And every time the young man, passing by, felt some kind of painful and cowardly sensation, which he was ashamed of and from which he winced.

He was hopelessly in debt to his landlady, and was afraid of meeting her.

He owed everything to his mistress and was afraid to meet her.

This was not because he was cowardly and abject, quite the opposite; but for some time past he had been in an overstrained irritable condition, verging on hypochondria.

It’s not that he was so cowardly and downtrodden, quite the contrary; but for some time he had been in an irritable and tense state similar to hypochondria.

He had become so completely absorbed in himself, and isolated from his fellows that he dreaded meeting, not only his landlady, but anyone at all.

He became so deeply involved in himself and secluded himself from everyone that he was afraid of even any meeting, not just a meeting with his hostess.

He was crushed by poverty, but the anxieties of his position had of late ceased to weigh upon him.

He was crushed by poverty; but even his cramped situation had recently ceased to burden him.

He had given up attending to matters of practical importance; he had lost all desire to do so.

He completely stopped his daily affairs and did not want to deal with them.

Nothing that any landlady could do had a real terror for him.

In essence, he was not afraid of any mistress, no matter what she was plotting against him.